Books

The First Fictional Female Detectives

Dr Lucy Worsley is a historian and Chief Curator of the Historic Royal Palaces, where she looks after the Tower of London! On Monday 7th October sees the last episode of A Very British Murder on BBC4 at 9pm. She’ll be looking at The Golden Age in the final episode and it’s well worth staying in for!

Lucy has taken some time out to write us a piece on the first fictional female detectives. As huge fans of Mrs Bradley and Miss Marple we love the focus on female sleuths (and are quite a bit jealous of Lucy’s outfit) over to Lucy Worsley:

Lucy Worsley

As an avid reader of crime stories, I’ve always had a soft spot for female detectives, with Nancy Drew, Harriet Vane and Miss Marple among my favourites.

What is it that readers particularly like about a lady sleuth? Describing the origins of his own heroine Mma Precious Ramotswe, Alexander McCall Smith has written that he chose a female lead because, if she were a man, ‘the conversation would be less interesting… less personal, less subjective − and less emotionally engaging’. McCall Smith is a compelling advocate for the pleasure to be found in following the success of a female detective. We take satisfaction in ‘seeing women, who have suffered so much from male arrogance and condescension, either outwitting men or demonstrating that they are just as capable as men of doing something that may have been seen as a male preserve’. And finally, a woman is very often overlooked and underestimated: ‘We suddenly realise that it is the woman who has seen and understood what is happening without ever being suspected of being a threat to anybody’.

What holds true of the great Mma Precious Ramotswe also applies to the very earliest female detectives to appear in fiction, back in the 1860s.

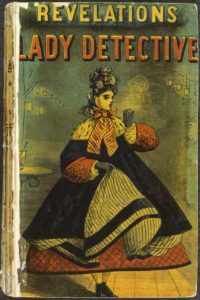

A great deal of debate has developed about the exact moment the first fictional female sleuth made her debut. But it’s generally agreed that The Female Detective, published in 1864 (or possibly in 1861) by Andrew Forrester (the pen-name of James Redding Ware) was the first work in this new genre. His character, Mrs Gladden, investigates crimes in a professional capacity, and is paid for her services. Another author, W.S. Hayward, was in close pursuit with Revelations of a Lady Detective, featuring another heroine who earns a living as a private eye.

Forrester and Hayward’s novels were published in a new and specialized form called the yellowback. These small, flimsy and semi-disposable novels took their name from their glossy covers with bright yellow borders. Costing sixpence (when a hardback novel would cost ten shillings) they were sold mostly on the railway stations that had sprouted up all across 1860s Britain. Promising a soothing interval of cheap entertainment, a yellowback from the bookstall seemed the perfect purchase for a traveller about to start, say, the ten-hour journey to Edinburgh.

Because they were made from such thin and cheap paper, very few yellowbacks have survived in good condition. But the British Library does have a copy of Hayward’s The Revelations of a Lady Detective, with its rather racy cover still intact. It could be that the author never selected or even saw the cover art, and, on the basis that ‘sex sells’, it shows a lady rather more racy than the detective herself featured in its pages. A nattily dressed lady is smoking, a very fast habit, and she’s also lifting up her skirts to reveal her ankles. The image bears a close resemblance to the Victorian ‘Haymarket Princesses’, the ladies of the night who worked around the theatres of London’s Haymarket, the revelation of the ankle beneath the skirt being the age-old indication of a prostitute.

This salacious image was obviously intended to tempt readers into buying a saucy tale, and it is true that the Lady Detective – although essentially sober and respectable – does some rather unladylike things. At one point, while chasing a villain, she finds it necessary to drop down through a hatch into a cellar. Her crinoline won’t fit through the hole, so she simply takes it off and abandons it. It’s a wonderful moment of female emancipation: freed from the ‘obnoxious garment’, as she calls it, she is able to get on with her work.

This is strikingly modern behaviour, and both the Lady Detective and Mrs Paschal, the Female Detective, are forceful, impressive characters. Mrs Paschal possesses great skill and knows it: verging upon forty years old, she has found a life-long calling in detection. She tells us that her brain is ‘vigorous and subtle’, and that she concentrates all her energies on her work. ‘I was well born and educated,’ she says, and ‘for the parts I had to play, it was necessary to have nerve and strength, cunning and confidence’.

But both detectives – and this is key – also have the ability to pass invisibly through the scenes of daily life. ‘The woman detective,’ explains the Lady Detective, ‘has far greater opportunities than a man of intimate watching, and of keeping her eye upon matters near where a man could not conveniently play the eavesdropper.’ To this end, the women play parts such as becoming a maidservant, to infiltrate an aristocratic household, or a nun, to spy on wrongdoers in a convent.

Here, right back in the 1860s, an important new strand of detective fiction was being spun: the crime-solver who blends into the background, like G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown, or, ultimately, my favourite Miss Marple. Hats off to these first fictional female sleuths!

A Very British Murder

A big thank you to Lucy Worsley for sharing her knowledge on the first fictional female detectives!

More information on A Very British Murder can be found here.

Follow Lucy Worsley on Twitter!

Read the Book:

2 Comments

Join the discussion

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.

It is refreshing to read about a female detective. It makes you see the story from a different perspective.