Books

Sarah Ward: giving victims a voice

I’ve not had too much difficulty killing off fictional characters in the past. A crime novel usually needs a murder and as long as I’m confident that I’ve not depersonalised the victim, and that I’ve shown the impact of the crime on their family and community, I feel confident that the dead aren’t forgotten in an investigation.

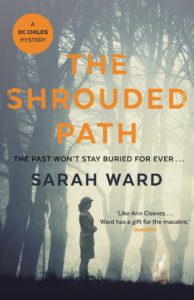

For my latest crime novel, The Shrouded Path, I wanted to write about the possibility of a Harold Shipman type figure operating in a close-knit community. I mentioned Shipman at a recent book event and a few people in the audience weren’t familiar with the name. Despite widespread coverage of the case, Shipman’s crimes are receding into the past. He was a doctor operating in Hyde, Greater Manchester, a man well-liked because of the rapport he developed with his patients. Women, in particular, sought out his practice through recommendations from friends and relatives, assured of a more caring, personal approach than they’d receive in larger GP practices. He was also one of Britains most prolific serial killers. He prayed on vulnerable patients and administered overdoses of morphine under the guise of pain relief.

For my latest crime novel, The Shrouded Path, I wanted to write about the possibility of a Harold Shipman type figure operating in a close-knit community. I mentioned Shipman at a recent book event and a few people in the audience weren’t familiar with the name. Despite widespread coverage of the case, Shipman’s crimes are receding into the past. He was a doctor operating in Hyde, Greater Manchester, a man well-liked because of the rapport he developed with his patients. Women, in particular, sought out his practice through recommendations from friends and relatives, assured of a more caring, personal approach than they’d receive in larger GP practices. He was also one of Britains most prolific serial killers. He prayed on vulnerable patients and administered overdoses of morphine under the guise of pain relief.

I deliberately haven’t used the term ‘elderly’ to describe the victims. An inquiry concluded that a child as young as four might have been among 250 former patients who died suspiciously under the GP’s care. However, older women constituted the majority of his victims and the implication of newspaper coverage of the time was these might have been mercy killings. Photos of the women concerned appeared in print as a sea of faces, blurring into a homogenous mass. In fact, many of Shipman’s victims were far from death and were just living with chronic illnesses.

When I came to write about the possibility of a Shipman-like figure in the Derbyshire community where I set my crime novels, I became preoccupied with giving my victims, all aged around seventy, strong identities. I wanted each woman to be shown as someone who was living an interesting and fulfilled life and who had left behind people who cared. What helped was the fact that these women were teenagers in the Fifties, which is also the decade where the impetus for the crimes in my novel can be found. It gave me a chance to show what it was like to be a teenager then: the trips to coffee shops, the stiff petticoats under calf-length skirts and the vibrant music. Studying black and white photos opened up the decade to me and brought these women to life.

The impact of Shipman’s crime was immense. Processes for certifying death were tightened as were dispensing practices by GPs. Sudden deaths were also investigated more thoroughly than they had been in the past, as I found out when my own mother died unexpectedly. The impression I get from speaking to GPs is that Harold Shipman would never get away with his killings now. I’m not so sure about that – crime usually finds a way – but writing about the legacy of Shipman made me realise how important it was to ensure that I gave this under-represented group of people a voice.

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.