Books

Peter Manuel: from fact to fiction

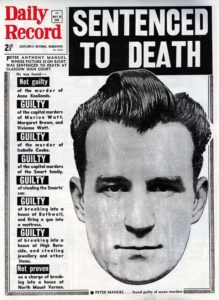

The chilling true story of serial killer Peter Manuel, subject of ITV’s recent three-part drama In Plain Sight, comes under the spotlight once again this month in a thrilling new crime novel by Denise Mina. Dubbed the Beast of Birkenshaw, a nickname coined by Manuel himself, the murderer claimed the lives of at least eight people during his two-year killing spree.

Manuel evaded capture for so long because he was unlike anything the local police had ever encountered: a murderer without any discernible motive whose victims were chosen at random. “If you didn’t put ‘This is a true story’ at the start of this, you wouldn’t believe it,” explains actor Martin Compton, who played Manuel in the recent dramatisation. “When you look at the details of the story and the fact he defended himself in court, it’s insanity. The sheer brazenness and confidence of the man was astonishing. He was the ultimate narcissist. An evil, evil man.”

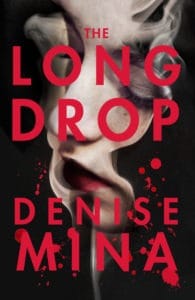

It’s perhaps no surprise then that such a horrifying character became the subject of a prime time TV show; as crime fiction fans, the reality that fact can often be worse than fiction is both disturbing and fascinating. But it’s not just television that has found inspiration in Peter Manuel’s case. Based on the true events, The Long Drop – the thrilling new novel by Denise Mina – reimagines what happened when Manuel met with William Watt, the father of the first family that suffered at the hands of the killer, one December night in 1957. We asked Denise to tell us how her interest in the case has inspired the book.

It’s perhaps no surprise then that such a horrifying character became the subject of a prime time TV show; as crime fiction fans, the reality that fact can often be worse than fiction is both disturbing and fascinating. But it’s not just television that has found inspiration in Peter Manuel’s case. Based on the true events, The Long Drop – the thrilling new novel by Denise Mina – reimagines what happened when Manuel met with William Watt, the father of the first family that suffered at the hands of the killer, one December night in 1957. We asked Denise to tell us how her interest in the case has inspired the book.

Over to Denise:

“Peter Manuel is a legend in Glasgow. People still whisper about him. The new ITV drama In Plain Sight tells the story of how he was caught and tried and hung but if you want to know why he still lingers in our collective imagination, you have to listen to the pensioners.

I had no choice but to listen to them. In 2013 I wrote a play about Manuel and they wouldn’t leave the theatre until they told me that I had the story wrong. They knew what had really happened and I was wrong, wrong, wrong. It was pretty embarrassing. It was only our mutual obsession with the case that tempered my blushes.

I first heard of Peter Manuel in the late 1980s, while doing a law degree at Glasgow University.

“During this time,” the Criminal Law lecturer chortled, “There was a fashion among accused criminals for dismissing their counsel and conducting their own defense.

“You may have heard the phrase ‘Any man who conducts his own defense has a fool for a client’. Well, they were mostly fools. But they were copying Peter Manuel, who wasn’t a fool and made a good stab at defending himself.”

The lecturer used these cases to illustrate the many ways in which criminal cases should not be conducted. It is not a proper defense to a charge of theft to prove that the judge is a homosexual. If charged with a drunken affray, it is not a defense to unveil a paranoid theory about the government. Conducting your own defense is not an opportunity to physically assault a complainant as they get down from the witness box. These things all happened in Glasgow courts after Manuel. His effect was far reaching.

Glasgow is spoiled for serial killers. Peter Brady is a native son, Fred West lived here, Peter Tobin is from nearby Johnston, but Peter Manuel still holds a peculiar horror. He is whispered about. Glaswegians have an engagement with the Manuel case that we don’t have with those other killers. We feel implicated. There are good reasons for that.

Manuel’s crimes are creepy. He broke into domestic houses and killed families, in one instance hanging around the house for days. He fed the cat and shut the curtains. He was seen at his own home during this time, which means that he went home and saw his family, ate meals with them and then returned to a house full of corpses and sat and was still. But actually, there is a fascination that is nothing to do with the gruesomeness of that story. The real fascination is with what actually happened.

Manuel’s crimes are creepy. He broke into domestic houses and killed families, in one instance hanging around the house for days. He fed the cat and shut the curtains. He was seen at his own home during this time, which means that he went home and saw his family, ate meals with them and then returned to a house full of corpses and sat and was still. But actually, there is a fascination that is nothing to do with the gruesomeness of that story. The real fascination is with what actually happened.

The resolution of the Manuel case does not make sense. It does not feel true.

In March 2013 my play “Driving Manuel” was staged at Oran Mor. It centered on the night that Manuel and William Watt spent driving around together in Glasgow.

William Watt was a successful businessman, the father of the first family killed in their beds. He had been imprisoned for their murders, despite having the cast iron alibi of being eighty miles away at the time. Released from prison, still under a shadow of suspicion and tainted in the public’s eye he ‘turned detective’ and began to investigate the case himself. He must have been watching a lot of movies at the time because he sounds like Sam Spade on a mission.

Watt let it be known in the Glasgow underworld that he would pay cash for information that led to the real killer. Roman Polanski did the same thing after his wife Sharon Tate was murdered. He was a suspect until the Mason family were caught.

I think this makes sense to anyone who reads or writes crime novels or detective fiction: it is a perfect set up. An innocent man under suspicion for a crime he did not commit must uncover the real killer.

One of those people who came forward with information for William Watt was the real killer. It was Peter Manuel and he wanted to meet William Watt.

Manuel met Watt in a restaurant, the lawyer who had facilitated the meeting left after ten minutes, and the two men were left alone.

They spend eleven hours together.

They drank all night. They moved from club to pub to Watt’s brother’s house at one point, where they had bacon and eggs. They drank tea in the car outside Manuel’s house. Manuel wouldn’t let Watt come in. He didn’t want to expose his mother to a man like William Watt who was in all the papers as a suspect in his family’s murders.

My play was about an innocent businessman who was playing at being a detective and was toyed with by a vicious, grandiose murderer keen to relive his sadistic crimes. It sold out for the run, was a great success, but a lot of the people who came to see it were pensioners.

Every single day I was accosted by people who had been alive at the time. They corrected me: the story was not black and white. I was wrong. William Watt was not an innocent in the murder of his family. He knew something.

It’s embarrassing to be wrong. To be wrong in public to a sold-out theatre for a full run of a play is very, very embarrassing but they were so adamant and they all said the same thing: William Watt was not the innocent he made himself out to be.

Embarrassment propelled me to read all of the newspaper coverage of the cases and the criminal court transcripts. At the end of it I knew that the pensioners were right.

I had the story wrong.

To understand what might have happened I had to speculate about the missing four hour period in Watt and Manuel’s night together, try to retrace their steps and work from the original confessions that Peter Manuel later retracted and contradicted. The result is my new novel, The Long Drop.

I hope the pensioners approve.

They’re quite scary en masse.”

Read the first chapter from The Long Drop by Denise Mina here.

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.