Books

Oscar de Muriel on Sherlock Holmes

Oscar de Muriel, author of the Frey & McGray novels The Strings of Murder and A Fever of the Blood, talks to us about the influence of Sherlock Holmes on his own Victorian mystery series.

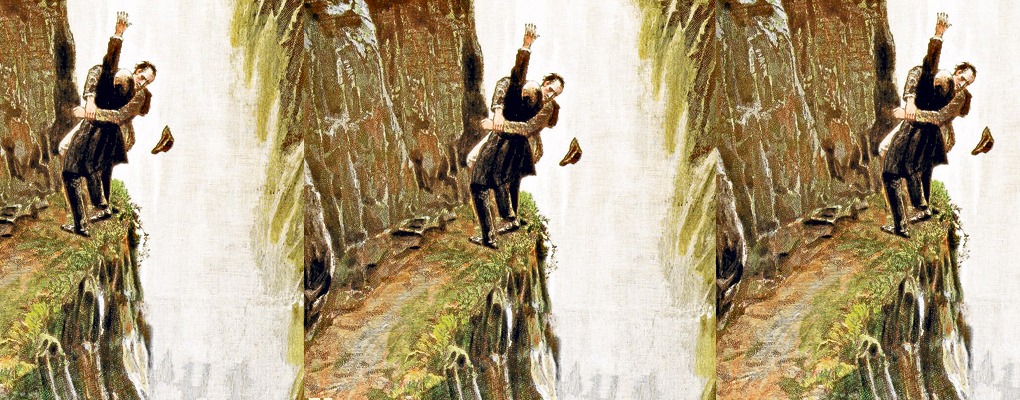

“Ever since my childhood and all the way through my adult life, I’ve spent endless hours curled up with a Sherlock Holmes. Such is my adoration of The Master that I can even forgive Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – as his creator – for trying so bloody hard to kill off my favourite literary hero.

Doyle wanted to write ambitious historical novels, to be a “respectable” author, not a peddler of mysteries. As deterrent to the publishers, Sir Arthur would demand eye-popping amounts of money for his stories, but The Strand paid him every time, without haggling a penny.

There’s an old Punch caricature where Doyle is shackled by a tiny Holmes, the character in control of its maker. When the frustration became too much, there was only one solution: murder. In 1893, “The Final Problem” was published. It was the death of Sherlock Holmes.

Yet the world couldn’t – and still can’t – get enough of our good old detective. The man at 221B Baker Street had taken on a life of his own and proved impossible to kill.

Yet the world couldn’t – and still can’t – get enough of our good old detective. The man at 221B Baker Street had taken on a life of his own and proved impossible to kill.

Eight years later, Sir Arthur found money far more tempting than literary scruples (for which I am extremely grateful) and wrote a prequel crime novel, which is my all-time favourite Sherlock Holmes case: The Hound of the Baskervilles.

To me, this story has the best thought-out plot – which is really saying something for a Sherlock Holmes story – one which makes the entire book shift in your head as soon as you read the denouement.

Along with the fiendishly clever mystery, it is the most atmospheric of all the Holmes stories. The Hound of the Baskervilles, possibly due to its length, has some beautifully evocative descriptive passages we don’t usually find in the short stories. Sir Henry Baskerville is welcomed to his newly inherited estate by “the high, thin window of old stained glass, the oak panelling, the stags’ heads, the coats of arms upon the walls, all dim and sombre in the subdued light.” The moon shines on the fog “like a great shimmering ice-field, with the heads of the distant tors as rocks borne upon its surface.”

Adding much to the atmosphere are all those hints at supernatural interventions – the family curse, the glimmering hound in the dark – which keep calling back to me more than any other case for Holmes and Dr. Watson. Something that I’ve always found fascinating is that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was obsessed with the occult. On the one hand, he wrote all these wonderful stories where his hero relies entirely on deduction, observation and science; on the other hand, Doyle himself clung to spiritualism and used clairvoyants – and it is well known he actually believed in  fairies! Much of this is thrown into this plot and from the very first pages Doyle taunts us with eerie warnings – “forbear from crossing the moor in those dark hours when the powers of evil are exalted.”

fairies! Much of this is thrown into this plot and from the very first pages Doyle taunts us with eerie warnings – “forbear from crossing the moor in those dark hours when the powers of evil are exalted.”

Those devilish omens are a perfect embellishment for the crime mystery game Doyle perfected. Gone were the days of A Study in Scarlet, where we poor readers had no possible way to know who’d done it. The plots were now part story, part jigsaw, almost interactive in nature: we compete with Sherlock; we want to solve the mystery as much as he does; we try to keep track of the clues and fear to skip even a line in case we miss a well-hidden clue.

Needless to say I drew much inspiration from this book. Sir Arthur married the supernatural and gothic elements with a superb murder mystery, and the mix was as effective and endurable as tequila and lime (sorry, I grew up in Mexico). Furthermore, the Victorian era, when superstition and rationality had equal pulls, lends itself to this mixture like no other. It was then that events like the industrial revolution and Darwin’s theories clashed against people’s most ancient beliefs and fears – very much like the conflict between Sherlock and his author. I wanted to have that debate well represented in my stories, hence the discordant personalities of my detective duo: Inspector Ian Frey (rational sceptic, snobbish Londoner) vs Detective ‘Nine-Nails’ McGray (superstitious Scotsman, open to all possibilities). When these two rant against each other it’s not just an argument between individuals, but between the two major schools of thought of their time.

Another source of inspiration was the barren landscape Sir Arthur describes so well. For The Strings of Murder, I explored almost every corner of Victorian Edinburgh, so I always knew that if Frey and McGray managed to get a second case they would go out of town. In A Fever of the Blood they travel all the way from Scotland to the Lancashire wilderness, facing everything from ghastly food and robbery to the worst blizzard in living memory.

Another source of inspiration was the barren landscape Sir Arthur describes so well. For The Strings of Murder, I explored almost every corner of Victorian Edinburgh, so I always knew that if Frey and McGray managed to get a second case they would go out of town. In A Fever of the Blood they travel all the way from Scotland to the Lancashire wilderness, facing everything from ghastly food and robbery to the worst blizzard in living memory.

Whilst plotting their new adventure it was great fun to follow their footsteps, although I must say their trip was far more tortuous than mine – country pubs in the nineteenth century could be very rough places! Unlike them, I simply grabbed some hiking maps and got lost in the Lancashire hills, where I had the pleasure to live until very recently. Despite being on the other side of the country (Hounds takes place in Devon), it was impossible not to picture Dr Watson walking along that countryside, looking at the English moors, oblivious of all the surprises that awaited him in such a – seemingly – desolate place. And I hope that A Fever of the Blood does justice to the genre immortalised by him and Mr Holmes – despite their creator’s best efforts to brush them off.”

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.