Books

Lost People, Lost Places

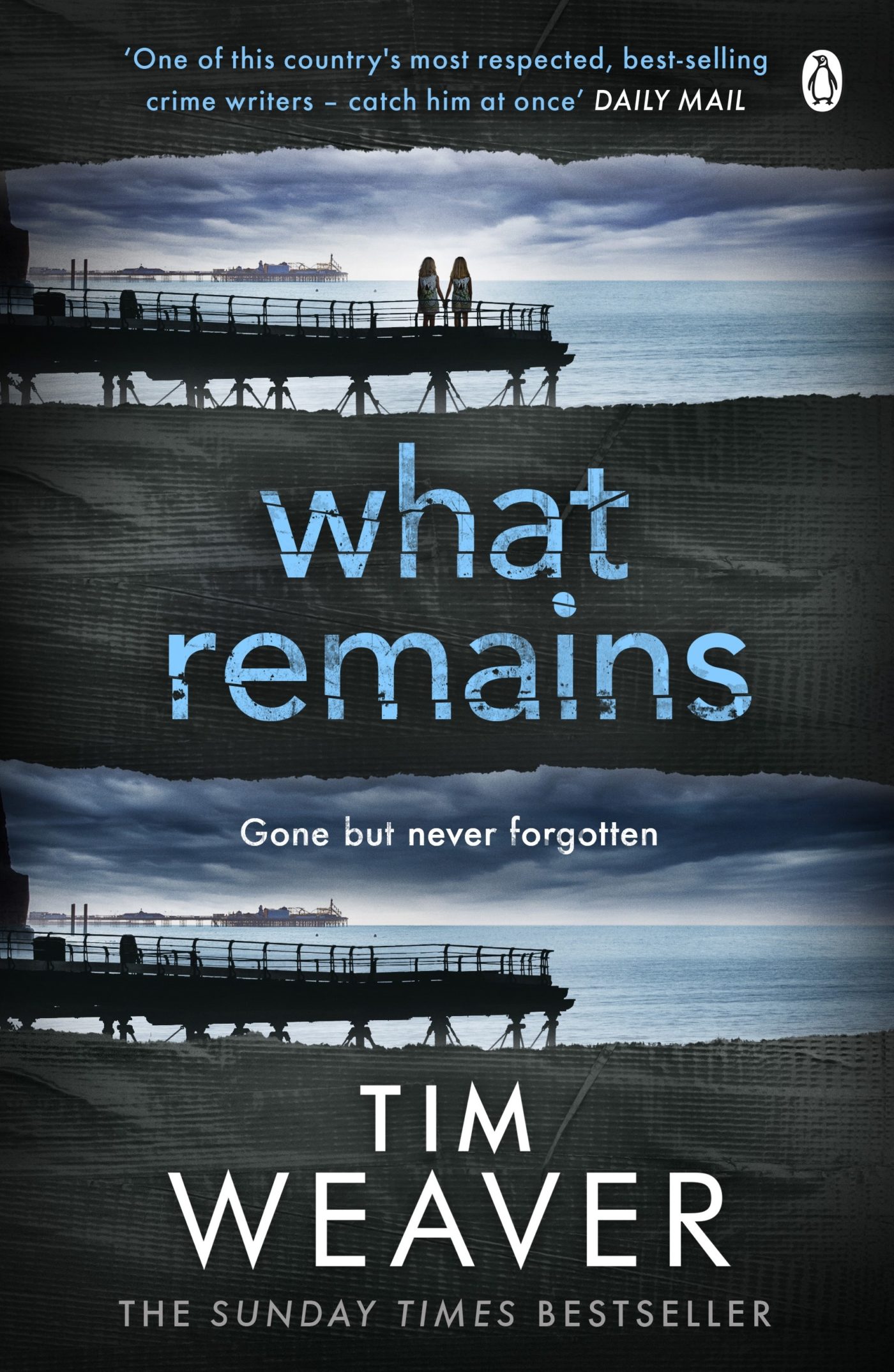

In What Remains, the sixth novel to feature his missing persons investigator David Raker, Tim Weaver continues to find inspiration not just in forgotten people, but in forgotten locations…

“I’ve been fascinated by abandoned places for as long as I can remember. It’s not something particularly unique to me – there’s a whole sub-culture based around accessing, photographing and documenting long-forgotten buildings, from old hospitals and asylums, to Tube stations, to theme parks, even entire cities.

In fact, interest in derelict architecture is so great that I’m not sure it’s even really a sub-culture anymore – when the Guardian, the Telegraph, Buzzfeed and Rough Guides have covered the subject, you know interest in the field has gone beyond a couple of blokes running around a World War 2 bunker in Dorset with a flask of coffee and a knackered instamatic.

I think part of the attraction for me is that these places reflect, in some ways, the man I write about, David Raker. As a missing persons investigator, a widower, an outsider (he started out life as a journalist, not a cop, so the police view him with suspicion), and in particular because – through a mixture of choice and circumstance – he remains something of a lonely soul, he has a certain affinity with the disappeared, the forgotten, the lost. In my new novel, What Remains, he overtly references the fact when describing an old pleasure pier, shut for over twenty-five years, but still standing:

“There was a strange sense of loneliness to the pier that was difficult to explain. I’d been to many places like this, inside structures that were nothing but skeletons, along corridors that were vessels for memories and the nightmares that had taken place in them. I’d even started to believe that, somehow, my years finding missing people had awoken something in me; a sort of magnetic pull. Maybe my own heartache marked me. Maybe these places sought me out now.”

Wapping Pier, one of the central pillars of What Remains, is imaginary, but it’s very much based on places that exist in real life. This, for me, is one of the most fascinating and rewarding aspects of writing the series: finding inspiration in somewhere that I’ve been to or seen, and – because the actual location doesn’t quite fit the plans I have for the story – creating a different, fictional version, remoulded and reshaped. In doing so, you have a responsibility to ensure it feels like a real place even if it isn’t one, with its own sense of history, its own identity and atmosphere; you have to spend time constructing a background narrative so that it feels like it exists – just as much as any living, breathing character.

I’ve done this a number of times. Highgate Overground Station was the inspiration for the entirely fictional ghost station at the entirely fictional Fell Wood in my third book, Vanished. In Never Coming Back, the abandoned village of Miln Cross was based on the tragic history of Hallsands. In Fall From Grace the island hospital, Bethlehem, came about as a direct result of stumbling across these evocative photos from inside London’s Cane Hill Asylum, and from spending time in and around Burgh Island in Devon (already famous for being the inspiration for Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None).

My fascination with old, decaying architecture has continued through to my latest novel, What Remains, where I sought inspiration in the old, pre-fire Weston-Super-Mare Grand Pier (which I visited many times as a kid), Birnbeck Pier, just down the road from it, and the Victorian Penny Arcade at Wookey Hole, which I found incredibly tacky and bit naff… but somehow – weirdly, indefinably – creepy.

Abandoned places always add a lovely sense of foreboding to a thriller, by the very fact that they’re quite often big spaces that are now isolated and empty – but, actually, when you spend enough time looking at real-life examples, there’s a strange sort of beauty to them too. Their decay is often like a deliberate work of art – the intricate patterns of peeling paint; exteriors being claimed back by the earth; colours slowly being leeched from powdery, crumbling walls – and the forsaken nature of old buildings, some of them beautiful examples of period architecture, is also quite somber too. Certainly, in writing about these places, I hope I manage to communicate their strange marriage of fear and melancholy.

As a writer, there are many things you hope readers might say about your book – that they loved your characters; that they couldn’t put it down; that the twists totally floored them, or a scene left them with a lump in their throat – but, for me, “Is that place real?” is always a wonderful thing to be asked. It means I’ve succeeded in creating a location that resonates, I’ve built it and fleshed it out with enough success that it feels like it could actually exist in the real world, and – perhaps most importantly of all – I’ve done some sort of justice to the incredible, forlorn and fascinating real-life examples of long-forgotten buildings.”

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.