Books

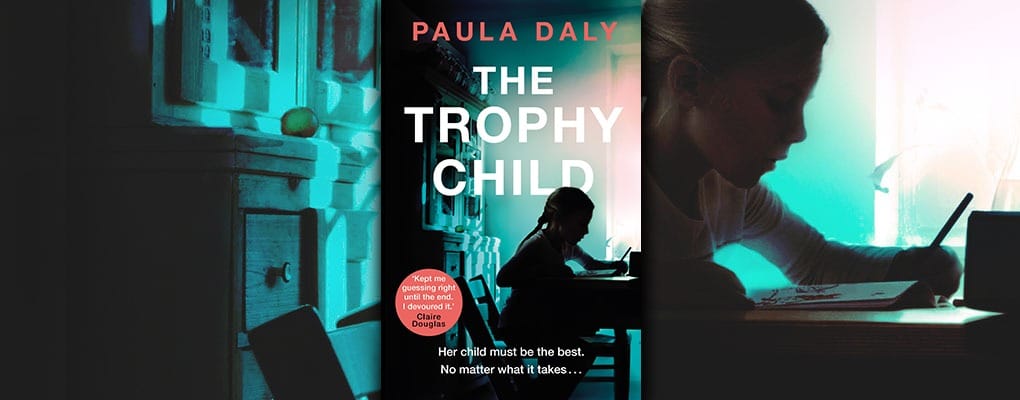

Extract: The Trophy Child by Paula Daly

The Trophy Child, Paula Daly’s latest gripping domestic thriller, explores how far a mother would go to achieve perfection, and the damage this can cause to a family.

Karen Bloom expects perfection. Her son, Ewan, has been something of a disappointment and she won’t be making the same mistake again with her beloved, talented child, Bronte. Bronte’s every waking hour will be spent at music lessons and dance classes, doing extra schoolwork and whatever it takes to excel.

But as Karen pushes Bronte to the brink, the rest of the family crumbles. Karen’s husband, Noel, is losing himself in work, and his teenage daughter from his first marriage, Verity, is becoming ever more volatile. The family is dangerously near breaking point. Karen would know when to stop… wouldn’t she?

Read on for an extract from The Trophy Child!

The Trophy Child

by

Paula Daly

1

Monday, 21 September

The girls’ changing room smelled heavily of sweat, mud and a sickly-sweet deodorant that was beginning to irritate the back of her throat. She didn’t have a lot of enthusiasm for hockey. Not a lot of enthusiasm for school, full stop, now that she was on a probationary period. It was to be a period of indeterminate length, during which her behaviour would be monitored by a variety of well-meaning professionals.

Verity Bloom: not quite a lost cause.

Not yet.

Everyone was doing their utmost to prevent a deterioration in her performance – not least the staff of Reid’s Grammar, because, up until recently, she had always been such a promising student.

‘We have so much invested in her,’ the head teacher had told her father. ‘We want her to realize her full potential, and it would be a travesty if a girl such as Verity was not given the proper support at what is clearly a very difficult time. A difficult time for all of you, in fact.’

They had left that meeting with her father stooped, a man beaten down by life, a man who was just so tired of it all. ‘You’ll do as they say?’ he’d asked, and Verity had shrugged her response in the way only a teenager can. ‘It’s this, or you’re out of here,’ he said.

‘Would that be such a bad thing? Maybe this isn’t such a great place after all.’

Her father had sighed hard.

‘It costs eighteen thousand pounds a year. In total, I’ve spent over seventy-five thousand pounds on your education here, just so you can come out with nothing . . . Christ, Verity.’

‘I wouldn’t come out with nothing,’ she’d argued. ‘I could do my GCSEs elsewhere.’

And he had held her gaze for such a long time, a deep, deep sadness forming in his eyes, that, finally, she’d said, ‘Okay.’

She’d said, ‘Okay. I’ll do it.’

Three weeks into the autumn term and the long summer break was fast becoming a distant memory. She removed her boots, her shin pads, her underwear, and made her way to the showers. She let the water run over her shoulders, the skin of her back; the temperature was kept just below optimal heat to prevent the girls from dawdling, to make certain they would be in time for the next lesson. Pointless, really. Sixteen-year-old girls were never so comfortable with their new bodies that they lingered in the communal showers. A few would try to get out of showering altogether. It had been that way since they had started secondary school, back in Year 7. But the PE staff had got wise to their excuses early on and now they documented them on a spreadsheet. Exemption from showering was not permitted two weeks in a row.

The head of girls’ PE put her head around the tiled wall and scanned the assorted faces before her until she found Verity. ‘Where do you need to be next period?’ she asked.

‘IT.’

‘You can be a few minutes late. Get out now and get dry. Come and see me when you’re dressed. I’ll be in my room.’

Verity nodded, exiting the showers to a flurry of whispers and stifled giggles.

Alison Decker was a serious-looking woman. Verity supposed you had to be to run a PE department. Every day, she wore black Ronhill running pants and a school-issue sweatshirt with her name emblazoned across the back, as though she were on a netball tour. (She did use to play for Cumbria.)

Verity liked her. She was straightforward; you knew where you were with her. Not like the vague, flaky dance teacher, whom the girls approached when they had a problem. Or the blondbobbed, overstyled woman they hired to coach tennis during the summer term. That woman had a sneaky way about her, and the students always felt as though she was listening in on their conversations. Alison Decker was too busy to eavesdrop. And, frankly, she couldn’t care less what the girls were saying. They were students. They were meant to be organized, disciplined and exercised. She did not want to know about their personal lives.

Which made her the perfect choice to administer the test.

Verity dressed quickly, keeping her head low. She was well aware that she was being watched by the others. They were pretending to talk among themselves, pretending they weren’t looking her way. An affected girl she shared a lab bench with in physics was showing pictures of baby sloths on her iPhone; her friends cooed excessively, made long, loud awwwwww sounds, as though they were infants once again and a puppy had been led into class.

Verity packed up her things and headed out to the main corridor. The bell was yet to sound, so it was empty save for a teacher at the far end. He was attaching a sheet of A4 to the music notice board. Once it was in place, he stood back, hands behind his head, to survey the rest of the announcements.

Reid’s Grammar was no longer a grammar school but had kept the title when it switched to independent status in 1977. It was positioned on the eastern shore of Windermere, at Countiesmeet, where the old counties of Lancashire over the sands and Westmorland used to join.

Reid’s was a good school. That’s what everyone said: ‘Reid’s Grammar is a very good school,’ and Verity was privileged to attend such an institution. She knew she was. And it was pretty idyllic. It occupied some of the most expensive land in the country. It had lake access, three jetties (belonging to the sailing school), two croquet lawns and a state- of- the-art livery where students could board their horses.

At Reid’s the students wore exactly the kind of uniform you would expect them to: the prefects black, billowing gowns; Years 7 to 11 brightly coloured striped blazers, the girls long, pleated skirts. They used to wear straw boaters in the summer months but these were jettisoned after a series of stealth attacks from the kids at the local comprehensive school in which the hats ended up in a variety of places – once, on the head of a boarding mistress’s horse, its long ears sticking out through holes that had been cut in the top.

For the most part, the pupils of Reid’s stayed out of trouble and the school was able to maintain its untarnished reputation.

For the most part.

The bell sounded and the corridor was immediately flooded with bodies.

‘You, boy!’ came a shout from behind Verity. ‘No running!’

Verity was swept along with the throng. Two boys from the year below, heading in the opposite direction, caught sight of her and immediately began pretending to strangle each other, their eyes crossing, tongues lolling out. Both shot her wicked grins as they passed. Verity stared right through them, taking a right down a side corridor and pausing before knocking on the frosted glass of Miss Decker’s door.

Decker must have seen her shadow through the glass because she threw the door open, telling her to come in. She did not invite her to sit down, instead gesturing that Verity should stand to the side of her desk until she had finished filling out the under-fourteens hockey team sheet for the match against Stonyhurst on Saturday.

Verity chewed on her lip and moved her weight to her other foot.

‘How are things at home?’ Decker said, without looking up. This caught Verity off guard, because Alison Decker never pried.

‘Okay,’ she said.

‘Okay good, or okay bad?’

‘About the same,’ said Verity.

Decker gave a curt nod. ‘Very well. We’ll wait for the start of the next lesson and then we’ll get on with it.’

Verity was aware that Decker didn’t have to extend her this courtesy. In fact, it was probably interfering with her schedule and would make her late for the next PE class.

‘You thinking of running cross-country again this year?’ Decker asked.

‘Haven’t made up my mind.’

‘It’d be a shame not to.’

Verity shrugged.

‘All right,’ Decker said. ‘I won’t hassle you. Let’s get this over with and get you on your way.’

She followed Decker to the girls’ toilets. The corridor was empty again. She hung back a little as she watched Decker walk in, pretty sure of what she’d find in there.

A moment later and Decker stopped dead in the doorway, her trainers squeaking to a halt.

It was really quite theatrical.

‘Do you three mind telling me what you’re doing?’ she demanded loudly.

‘Nothing, miss . . .’

‘Sorry, miss.’

‘We just needed to . . .’ came the voices from within.

Verity watched as three Year 11 girls exited in a cloud of perfume. They were heavily caked in fresh make- up and scowled upon seeing Verity, as the real reason for Decker’s presence registered.

‘If I catch you in here again when you’re supposed to be in lessons, I’ll wash that muck off your faces myself!’ Decker shouted to their backs, and they hurried away.

Once inside, Decker withdrew a container from her pocket and said, ‘Quick as you can now, Verity,’ and Verity took it from her silently, without meeting her eye.

Urinating into a beaker, aged sixteen, when your PE teacher is on the other side of the cubicle door, had to be one of life’s low points. It was mortifying for Verity, handing over the still-warm sample. Alison Decker took it from her, her face a perfect mask of indifference, when Verity knew she must be repulsed, and wondering how this weekly task had landed at her feet.

‘Let’s go,’ Decker said.

Verity followed her back to her office, neither of them speaking, and waited as she unlocked the ancient grey filing cabinet and took out the drug-testing kit from the middle drawer. Surprisingly, you could buy them on Amazon now. They were not expensive and were easy to do. This was part of the deal Verity’s father had struck with the head. They would allow her to continue her studies, remain part of the school, if she agreed to weekly on-site drug tests and attended biweekly counselling sessions.

Verity did try telling them that she wasn’t into drugs – that she had never been into drugs, so all of this was rather unnecessary. But it didn’t seem to matter.

A minute passed. ‘You’re clean,’ Decker said. ‘Keep up the good work, Verity.’

‘You betcha.’

Then Decker hesitated, as if what she was about to say was painful in some way.

‘I’m here, Verity,’ she said eventually. ‘If you need to talk . . . anything like that.’

Decker had been told to say this. The woman did not want to be Verity’s sounding board, any more than Verity wanted her to be.

‘I’m okay,’ Verity said, offering a benign smile.

‘As you wish, Verity. Probably for the best.’

2

Detective Sergeant Joanne Aspinall scanned the hotel bar for signs of her date. She wondered, not for the first time, if people really did enjoy eating out and long walks in the countryside or if that was something they wrote on their profiles when they were too embarrassed to write the truth. Would anyone reply if Joanne were to write: ‘Overworked copper, generally too tired to socialize, recently dumped by colleague, lives with aunt, not very good with kids.’

Probably.

She’d most likely get some weirdo who had a fetish for slightly sad, exhausted women.

A colleague from work, an officer in the mounted police, had recently been out with a guy from a dating site. He’d asked her to post her dirty underwear to a sales conference he was attending in Devizes. To remind him of her while he was working.

Joanne hadn’t told the truth on her profile page. She’d ended up plumping for the standard ‘long walks’ and ‘eating out’ in an attempt to lure someone relatively normal. And it had taken weeks to arrange a date. One date. It should have been simple. But it had become evident to Joanne almost immediately upon joining secondchance.com that most people were not looking for love. They were looking for no‑strings sex. She had spent far too many hours sifting through profiles, answering questions about herself from prospective suitors, when she could have been sleeping:

If you could change one thing about your appearance, what would it be?

Joanne did think of responding with the truth. Saying that she’d already changed the thing that needed changing – by way of breast-reduction surgery. But she got the impression that when a man asked that type of question he was hoping for an answer more along the lines of: ‘I’d change my bee-stung, porn-star lips and tendency to be promiscuous when drunk.’

So Joanne had played it safe and moved on to the next candidate.

Which is how she ended up chatting online to Graham Rimmer.

Graham Rimmer, who was now quite late.

Joanne hadn’t told him she was in the police. It wasn’t something to volunteer on a first meeting, as she would most likely be pressed for information, and she certainly didn’t want to talk shop all evening. Also, when people found out she was a detective they were in the habit of becoming rather jumpy and restless. As though she could see straight into their souls, and discover all manner of dirty secrets. Like a psychiatrist. Or a pub landlord.

Joanne signalled to the waiter. The hotel bar was busy, but he’d been glancing her way every few minutes. He knew she had a booking in the restaurant for two, and Joanne suspected that her body language was giving her away, making it obvious that she was on a first date. A first date with someone she couldn’t guarantee looked anything like his profile picture.

Graham Rimmer had told her he worked for the National Trust, managing a large area of land close to Ullswater in the North Lakes, and Joanne had thought that sounded rather sexy, in a Lady Chatterley/Mellors kind of way.

That’s if he’d told her the truth. And since she had listed her occupation as ‘bookkeeper’, she could hardly complain if it turned out to be nonsense.

‘What can I get you?’ the waiter asked.

‘Small Cabernet Merlot, please.’

‘Sure I can’t get you a large?’

‘I’m driving.’

Joanne checked her watch. It was 8.23, and a few couples were making their way from the bar area through to the restaurant to dine. She fiddled with her phone, checking it once more, hoping to see: ‘Be there in five minutes!’ Except that would be a miracle, since she’d not given Graham Rimmer her number.

‘Here you are,’ the waiter said, placing the glass down in front of Joanne. ‘Can I get you anything else while you wait? Some olives, perhaps? Some—’

‘I’m fine as I am.’

A lone guy at the bar turned around on hearing their exchange and then quickly away when Joanne shot him a look. He’d had two glasses of whisky since Joanne had arrived and she wondered if he was planning to drive tonight. He didn’t seem like a guest. He wore a shirt and tie – the tie pulled loose – and he looked as though he’d been in the same clothes since morning. If Joanne had to hazard a guess, she would say he’d called in here to delay going home. He was easy on the eye, she noticed.

Then Graham Rimmer arrived.

And Joanne’s heart sank. He was a bloated-fish version of his profile picture and, as he approached the table, he was out of breath, wheezing a little. He did not appear to be the type of person who was used to rebuilding dry-stone walls and untangling Rough Fell sheep from thorny hedgerows.

He thrust out his hand. ‘Joanne – Graham. Pleased to meet you. Sorry I’m late.’

No explanation as to why.

He removed his leather jacket, a heavy, ancient, biker thing, and slung it around the back of the chair. The weight of it made the chair start to topple, but Graham caught it in a way that made Joanne think it happened often. ‘Just get myself a drink. Back in a sec,’ he said.

He made his way to the bar and ordered a pint of Guinness. As he waited for it to pour he thrust his hands in his pockets and rocked to and fro from the balls of his feet to his heels.

Joanne willed herself not to make a hasty judgement, but this was all wrong. The man on the dating site had seemed mild-mannered, gentle. This guy was boorish: the total opposite to what she had expected. He was also substantially older than his photograph had suggested, and around four stone heavier.

Graham took two large swallows of his pint before heading back towards Joanne.

Wiping the froth from his lipless mouth on the back of his forearm, he seated himself noisily, saying, ‘So, bookkeeping, then. Bet you’re glad to get out and about if you’re stuck in front of a computer all day. Wouldn’t suit me. I like the outdoors. Not that I get out as much as I used to. When you’re in management, you tend to lose touch and end up in too many meetings. But hey‑ho – it could be worse. You got any kids, Joanne, love?’

‘No, I—’

‘I’ve four. Two big, two small. Two ex‑wives as well, who bleed me dry, but I won’t go into that. It’s not polite talk for a first date. Not that we need to be polite. Best to show who we are up front. I’m always the same with everyone. No airs and graces. What you see is what you get. Have you been here before? The beer’s pricey.’

‘My first time.’

‘Mine, too. Might be the last. You say you’re from Kendal?’

‘Not far from—’

‘I was born in Penrith. Never travelled far. Never saw the need. People are the same wherever you go. What do you do when you’re not working? I don’t do a lot. Don’t get a chance, really. I should. I know what you’re thinking. How am I going to meet someone if I don’t get myself out there?’ He made a wide, sweeping gesture, as if the world beyond the bar held all the answers to his single status. ‘I didn’t cheat on my wife.’ He coughed. ‘Sorry, wives . . . if that’s what you’re thinking. Though, God knows, I had more than enough opportunity. The first one said she didn’t cheat on me but, well, she waited the standard six weeks, and hey presto, she’s shacked up with someone else. Brian. Delivers cooked meats. Thought he was a mate. I don’t hold a grudge. No point. Life’s too short. Anyway, what was I saying? The second one, well she was a proper dragon. Married her on the rebound. I won’t do that again – marry in a hurry. No offence.’

‘None taken.’

‘To be honest, I think she was a bit deranged. She’d not exactly been abused as a kid, but her mother used to hit her with a wooden spoon and lock her in the airing cupboard. Sometimes overnight. I think it left its mark. I tried with her. I really did. No one could say otherwise. When I think what I went through to make that woman happy. Anyway, you don’t want to hear all this. As long as we stay off politics, eh? What? No, I think Cameron’s a tosser. You can’t have a bunch of rich bastards running the country, can you? It’s not right. Farmers get a raw deal every time. I don’t know why more don’t stick a shotgun in their gob and end it.’ He stopped momentarily to drain the rest of his pint, before telling Joanne that this dating business was thirsty work and, ‘I’ll just go and get myself another.’

Joanne thought about leaving. She could get in her car and go. Leave Graham Rimmer to talk to himself for the rest of the night. Or she could disappear to the ladies’ and hide. The thought of a whole evening spent with him was beginning to fill her with a sickening kind of dread, but how does one get out of a situation such as this? If she’d been straight from the start and told him she was a detective she could have invented an excuse. An emergency at work. A murder. She could have left, him thinking no worse of her, or of himself for that matter. But, as it was, she couldn’t come up with a suitable emergency that might arise from the world of bookkeeping.

A fine sweat sprung up on Joanne’s lip and, as she reached inside her handbag to find a tissue, she saw the small Phillips screwdriver and the mace. Items she’d packed tonight in case her date turned out to be a demented woman killer. Funny, but that prospect had seemed a lot more likely than the need to escape a boring, overweight guy who was more likely to talk Joanne to death.

She glanced towards the bar. In the time it had taken for the Guinness to pour, Graham Rimmer had struck up a conversation with the whisky drinker in the loosened tie one seat along. He was explaining that he was on a first date and he seemed to have landed lucky, as he hadn’t expected much from someone he’d found on the internet. ‘Thought it’d be just the dregs,’ he said.

Graham Rimmer made his way back to Joanne’s table, this time neglecting to wipe the foam from his upper lip and giving Joanne a broad grin as he seated himself, telling her she had a smashing shape for a woman of forty.

All at once, Joanne felt not forty but very, very old.

Was this what her life had come to? A succession of dates like this? With men like this?

She could imagine being in bed with Graham Rimmer, him farting loudly, saying, ‘Did you like that?’, impersonating steeplejack Fred Dibnah on felling a chimney, finding himself utterly hilarious.

‘You don’t say much,’ Graham Rimmer said.

Joanne tried to smile. ‘Maybe I’m a little nervous.’

And he reached out and put his hand on hers. Covered it with his big, meaty fingers.

Giving her hand a firm squeeze, he said, ‘No need to be nervous of me, love. I won’t bite . . . Not unless you want me to, anyway.’

Joanne removed her hand.

‘I had something of a dalliance in between my marriages,’ he said, dropping his voice a level. ‘With a kennel maid from Wigton. Too young for me, really, but she was keen enough so I went with it. Sometimes she liked me to bite her on the—’ He paused here, looking furtive, before motioning over his shoulder with his thumb.

‘On the back?’ asked Joanne.

‘On the bottom,’ he said. Then he frowned, blowing out his breath. ‘I thought it was strange, and I’ve got to say I wasn’t proper comfortable with it, but you know what they say. Takes all sorts.’

Indeed it does.

Joanne shifted in her seat and straightened her spine. ‘Graham,’ she said, again trying to smile a little, ‘you know you listed your age as forty-seven on your profile? Well, if you don’t mind my saying, you do look a bit older than that. How old are you, exactly?’

Graham put down his pint.

‘Sixty-one.’

He arched an eyebrow and looked at Joanne expectantly. It occurred to Joanne that he was waiting to be complimented on his appearance. In another situation, she might have gone along with it, just to be polite.

Instead she said, ‘You didn’t think it might be unfair to lie?’

‘Doesn’t everyone lie about their age?’

‘No, Graham,’ Joanne said. ‘No. They don’t.’

For a moment Graham looked abashed, staring silently at his beer. Then he said, ‘I think you’ll find I’m a very youthful sixty-one.’

And Joanne replied, ‘I’m sure you are. But, Graham, I’ve got to be straight with you. I’m in the market for someone a bit younger.’

He lifted his head.

‘Oh, you are, are you?’ he said, indignation clear in his voice.

‘Yes. I am.’

Graham was put out. He ran his eyes over her disdainfully, as though to say, Don’t hold your breath. Then he cleared his throat and stood.

‘Well, if that’s the way it is,’ he said. ‘If that’s the way it’s going to be, then I don’t suppose it’s worth buying you dinner, is it?’

‘Probably not.’

Graham grabbed his jacket and departed without saying goodbye, and Joanne was left feeling quite embarrassed, but relieved nonetheless. She would not be doing this again. It had taken too much time and energy to arrange this date, only to get to the point where it was clear there was a lot more to be said for spotting someone across a crowded room, someone who stirred your interest for no logical reason that you could fathom.

Commenting on profiles, waiting days for emails to be returned, exchanging cagey details about yourself, was not how Joanne wanted to conduct her romantic life. And if Detective Inspector McAleese hadn’t got cancer she wouldn’t have had to, but he had promptly brought their relationship to a close upon receiving his diagnosis. Joanne had thought this was overkill at the time, as he’d been given great odds. His doctors had removed a short section of bowel and were doing chemo only as a precautionary measure. He was expected to make a complete recovery.

But McAleese had been insistent. ‘It’s over, Joanne,’ he had told her solemnly. She hadn’t been heartbroken. Just sad. Pete McAleese said his intention had been to save her from heartbreak. He didn’t want Joanne putting her life on hold while he fought a battle, a battle of indeterminate length, and Joanne had protested, saying that she wouldn’t be putting her life on hold at all. Her life was with him now.

But he wouldn’t have it. And Joanne had felt like she’d fallen straight into a movie from the fifties: tearful kid on a wraparound porch instructing the stray dog to ‘Go! Just get away from here. Y’hear me?’

Joanne was the dog.

The waiter appeared at Joanne’s side like an apparition. As if from nowhere. She must have been lost in thought.

‘The gentleman over at the bar sent you this,’ he said, his eyes dancing as he proffered Joanne a glass tumbler.

Joanne was taken aback.

‘What is it?’ she whispered.

‘Whisky. Glenlivet. He said he thought you could use it.’

Joanne felt heat rise in her cheeks. ‘Oh, I shouldn’t, really,’ she blustered. ‘I’m not really supposed to be . . .’

She tried to gather herself.

‘Please tell him thank you,’ she said firmly.

‘Why don’t you tell him yourself,’ he said, nodding his head towards the empty stool at the bar. Then he added in her ear, ‘He seems like a nice guy.’

Joanne stole a glance across. The man had his back to them, and he did not turn around like some leering idiot, tipping the rim of his glass her way. Instead, he was slouched forward, elbows resting on the bar. She had known instantly he wasn’t Graham Rimmer when she entered the room earlier, as his manner suggested he was killing time rather than waiting for someone.

Unlike Joanne, that is, who had sat erect in her seat, watchful, hopeful, eagerly examining everyone who entered.

She still had almost a full glass of wine in front of her. But she left it there on the table and picked up the whisky, carrying it, along with her jacket and handbag, over to the empty seat next to the man.

When she reached the bar, he turned his head her way and offered her a lazy smile. ‘Rough date?’ he asked, and she nodded.

‘Mind if I sit?’ she said.

‘Go ahead.’

She arranged her jacket on the stool and dropped her handbag against the foot of the bar. Lifting the glass to her lips, she said, ‘Thanks for this, by the way,’ and he tilted his head as though to say, It’s nothing.

They sat in silence. Joanne felt herself relax for the first time all day. She was working on a particularly frustrating drugs case. Their suspect, a slippery bastard who had a number of aliases but was known to Joanne mostly by his street name, Sonny, was moving heroin and assorted pills through Joanne’s area. He used a variety of women to hold on to his supply, but they didn’t know who or where these women were.

Joanne took another mouthful and let the tension ease from her shoulders.

Her drinking partner drained his glass and motioned to the barman for another. If he drove away from here tonight, Joanne would have to arrest him.

He turned to her. ‘Was it a blind date?’ he asked.

‘Kind of. I’d seen a photograph of him, but it wasn’t exactly what you’d call a true likeness.’

‘A dating website?’

She nodded.

She took a surreptitious peek at his left hand and saw it was devoid of a ring. The skin between each of his fingers was bleached. There were also patches of white skin on each knuckle and fingertip. ‘Have you ever tried it?’ Joanne asked. ‘Internet dating, I mean.’

‘Can’t say I have.’

‘That’s a shame. You could have given me some tips.’

He seemed amused.

‘You don’t need any tips,’ he said. ‘Just stick to people you like the look of.’ And then he held her gaze for one, two . . . three seconds.

Was he coming on to her? Joanne was so out of practice she really couldn’t tell. And yes, sticking to people you liked the look of was all very well, but when you didn’t actually come across many people you liked the look of in your daily life, then you resorted to sifting through online profiles in your dressing gown, your aunt watching over your shoulder, tutting and sighing at the slim pickings on offer.

‘I’m Seamus,’ he said.

‘Joanne.’

‘It’s good to meet you, Joanne.’

He didn’t offer his hand, just smiled again, and Joanne could feel the pulse in her neck begin to throb. She put her fingers there to cover it.

‘Are you a guest here?’ she asked.

‘Just stopped by on my way home. It’s been a long day.’

‘What do you do?’ she asked.

‘Accounting.’

Great. Bookkeeping was now a no‑go.

‘Do you live far?’ she asked.

‘Half an hour or so.’

‘You probably shouldn’t have that whisky if you’re driving.’

‘You’re right,’ he said. ‘I probably shouldn’t . . . but I will.’

A moment passed, and Joanne thought she’d made a mistake. He wasn’t coming on to her; he was just a decent guy who felt sorry for her. Plenty of those around.

‘Perhaps you’ll have to stay here a while longer,’ he said. ‘Keep me company until the alcohol’s worked its way out of my system.’

‘Oh?’ she said.

‘Or we could have dinner, if you haven’t eaten.’

‘I haven’t eaten.’

Seamus had accountant’s hands. Smooth skin with long, fine fingers. Hands that hadn’t done a lot of manual labour. Joanne put him at around forty-eight, and you could tell he was the kind of man who had been attractive in his youth, but there was a pull of worry around his mouth, as if life had taken its toll.

Did she fancy him?

Sure she did.

She took another mouthful of whisky. Again, they were silent.

Very few people Joanne came across were content to sit in total quiet. Apart from, that is, the occasional guilty, reprobate teenager she had to question. Always your typical unhappy customers. They hated the police and had no problem showing it. They didn’t even say ‘No comment,’ taking their right to silence to its fullest extreme.

‘Have you been on your own long?’ Seamus asked her.

‘You mean single? Not too long. I was in a relationship with a colleague, but it came to an end because . . . well, it just ended. How about you? Are you single?’

‘Yes.’

‘How long alone?’ she asked.

‘A long time,’ he said. ‘Too long.’

‘Too long without a relationship, or too long without a woman?’ she said, and Seamus shot her a mischievous, guilty look, as if to say, Ah, you got me.

Then he told her he’d not been in a relationship for several years.

‘Any particular reason?’ she asked.

He smiled. ‘Didn’t find anyone I liked the look of. Anyway,’ he said, pushing his glass away, rising from the bar stool, ‘shall we eat?’

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.