Books

Extract: Prague Nights by Benjamin Black

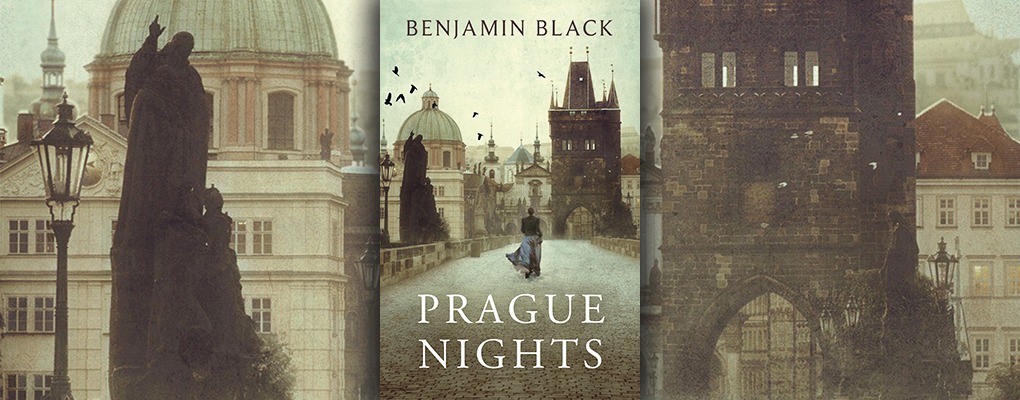

Prague Nights by Benjamin Black is a chilling historical mystery set in 16th-century Prague.

Christian Stern, a young doctor, has just arrived in the city when, on his first evening, he finds a young woman’s body half-buried in the snow.

The dead woman is none other than the emperor’s mistress, and there’s no shortage of suspects. Stern is employed by the emperor himself to investigate the murder. In the search to find the culprit, Stern finds himself drawn into the shadowy world of the emperor’s court – unspoken affairs, letters written in code, and bitter rivalries. But can he unmask the killer before they reach their next victim?

Read on for an extract from Prague Nights!

Prague Nights

by

Benjamin Black

I

December 1599

1

Few now recall that it was I who discovered the corpse of Dr Kroll’s misfortunate daughter thrown upon the snow that night in Golden Lane. The fickle muse of history has all but erased the name of Christian Stern from her timeless pages, yet often I have had cause to think how much better it would have been for me had it never been written there in the first place. I was to soar high, on gorgeous plumage, but in the end fell back to earth with wings ablaze.

It was the heart of winter, and a crescent moon hung crookedly over the bulk of Hradcˇany Castle looming above the narrow laneway where the body lay. Such stars there were!—like a hoard of jewels strewn across a dome of taut black silk. Since a boy I had been fascinated by the mystery of the heavens and sought to know their secret harmonies. But that night I was drunk, and those gemlike lights seemed to spin and sway dizzyingly above me. So addled was I, it’s a wonder I noticed the young woman at all, where she lay dead in the deep shadow of the castle wall.

I had arrived in Prague only that day, passing under one of the city’s southern gates at nightfall, after a hard journey up from Regensburg, the roads rutted and the Vltava frozen solid from bank to bank. I found lodgings at the Blue Elephant, a low establishment in Kleinseite, where I asked for nothing but went at once to my room and threw myself onto the bed still in my travelling clothes. But I could not sleep for a multitude of lice making a furtive rustling all round me under the blankets, and a diamond merchant from Antwerp, dying in the room next to mine, who coughed and cried without cease.

At last, bone-weary though I was, I rose and went down to the taproom and sat on a stool there in the inglenook and drank schnapps and ate bratwurst and black bread in the company of an old soldier, grizzled and shaggy, who regaled me with blood-boltered tales of his days as a mercenary under the Duke of Alba in the Low Countries many years before.

It was after midnight and the fire in the grate had died to ash when, far gone in drink, the two of us had the idea, which seemed a capital one at the time, of venturing out to admire the snowbound city by starlight. The streets were deserted: not a creature save ourselves was fool enough to be abroad in such bitter cold. I stopped in a sheltered corner to relieve my bursting bladder and the old fellow wandered off, burbling and crooning to himself. A night bird swooped overhead through the darkness, a pale-winged, silent apparition, no sooner there than it was gone. Buttoning my breeches—not an easy thing to do when you are drunk and your fingers are freezing—I set off on what I thought was the way back to the inn. But at once I got lost in that maze of winding streets and blind alleys below the castle, where I swear the stench of night soil would have driven back the Turk.

How, from there, I managed to end up in Golden Lane is a thing I cannot account for. Fate, too, is a capricious female.

I was a young man still, barely five and twenty, bright, quick and ambitious, with all the world before me, ripe for conquest, or so I imagined. My father was the Prince-Bishop of Regensburg, no less, my mother a serving girl in the Bishop’s palace: a bastard I was, then, but determined to be no man’s churl. My mother died when I was still a babe, and the Bishop fostered me on a childless couple, one Willebrand Stern and his shrew of a wife, who bestowed on me their name and sought to rear me in the fear of the Lord, which meant half starving me and beating me regularly for my supposedly incurable sinfulness. I ran away more than once from the Sterns’ cheerless house on Pfauengasse, and each time was captured and brought back, to be thrashed again, with redoubled vigour.

I had from the start a great thirst for knowledge of all things, and in time I became a precocious adept in natural philosophy and an ever-curious if somewhat sceptical student of the occult arts. I was fortunate to have got a sound education, thanks to my father the Bishop, who insisted I attend Regensburg’s Gymnasium, although foster-father Stern had preferred to apprentice me straight off to a farrier. In school I excelled at the quadrivium, showing a particular bent for arithmetic, geometry and cosmological studies. As a student I was both hard-working and clever—more than clever—and by the age of fifteen, already taller and stronger than my foster-father, I was enrolled in the University of Würzburg.

That was a happy time, maybe the happiest of my life, up there in gentle old Franconia, where I had wise and diligent teachers and soon amassed a great store of learning. When my years of study were done I stayed on at the university, earning a living of sorts by tutoring the dull-witted sons of the city’s rich merchants. But a life in the academy could not for long satisfy a man of my wilful and singleminded stamp.

The Sterns had been sorry to see me leave for Würzburg, not out of fondness for me but for the reason that, when I went, so too did their monthly stipend from the Bishop. On the day of my departure I made a vow to myself that my foster-parents would never set eyes on me again, and that was one vow I kept. I was to return to Regensburg once only, a decade later, when the Sterns were dead and there was an inheritance to collect. The legacy was a matter merely of a handful of gulden, hardly worth the journey from Würzburg, but it was enough to pay my way onwards to Prague, that capital of magic towards which I had yearned all my life.

The Bishop himself was recently dead. When with ill grace I had fulfilled my duty and visited his last resting place and, with greater unwillingness, that of the Sterns, I quitted Regensburg as fast as my old nag would carry me. In a calfskin pouch lodged next to my breast I carried a letter of commendation, which I had requested of His Grace when he was dying, though with small hope of being obliged. But on his deathbed the great man summoned a scribe to draw up the document, which he duly signed and dispatched post-haste to his importunate son.

This favour from my father was accompanied by a substantial purse of gold and silver. The letter and the money surprised me: as I was well aware, I was by no means the best-loved among his numerous misbegotten offspring. Perhaps he had heard what a scholar I had made of myself and hoped I might follow in his footsteps and become a prelate. But if that was what the old man thought, then by God he did not know his son.

He also sent me—I found it only by chance in the bottom of the purse—a gold ring that I think must have belonged to my mother. Could it be that he had given her this plain gold band as a secret token of fondness—of love, even? The possibility disturbed me: I had determined to think of my father as a monster and did not wish to have to think again.

And so I came to Prague, at the close of the year of Our Lord 1599, in the reign of Rudolf II, of the House of Habsburg, King of Hungary and Bohemia, Archduke of Austria and ruler of the Holy Roman Empire. That was a happier age, an era of peace and plenty before this terrible war of the religions—which has been raging now for nigh on thirty years—had engulfed the world in slaughter, fire and ruin. Rudolf may have been more than a little mad, but he was tolerant to all, holding every man’s beliefs, Christian, Jew or Mussulman, to be his own concern and no business of state, monarch or marshal.

Rudolf, as is well known, had no love for Vienna, the city of his birth, and he lost no time in transferring the imperial court to Prague in—ah, I forget the year; my memory these days is a sieve. Yet I do not forget my aim in coming to the capital of his empire, which was no less than to win the Emperor’s favour and secure a place among the scores of learned men who laboured at His Majesty’s pleasure, and under his direction, in the fabulous hothouse that was Hradcˇany Castle. Most were alchemists, but not all: at court there were wise savants, too, notably the astronomer Johannes Kepler and the noble Dane Tycho Brahe, Rudolf’s Imperial Mathematician, great men, the two of them, though of the two Kepler was by far the greater.

It was no easy goal I had set myself. I knew, as who did not, Rudolf’s reputation as a disliker of humanity. For years His Majesty had kept to his private quarters in the castle, poring over ancient texts and brooding in his wonder rooms, not showing himself even to the most intimate of his courtiers for weeks on end; he had been known to leave envoys of the most illustrious princes to cool their heels for half a year or more before deigning to grant them an audience. But what was that to me? I meant to make my way into the imperial sanctum without hindrance or delay, by whatever means and by whatever necessary stratagems, so large were my ambitions and so firm my self-belief.

Thoughts of royal favour were far from my mind that night in Golden Lane. I stood swaying and sighing, my mind fogged and my eyes bleared, peering in drunken distress at the young woman’s corpse where it lay asprawl in the snow.

I thought at first she was old, a tiny, shrunken crone. I was unable, I suppose, to conceive that anyone so young could be so cruelly, so irreclaimably dead. She lay on her back with her face to the sky, and she might have been studying, with remote indifference, the equally indifferent scatter of stars arched above her. Her limbs were twisted and thrown about, as if she had collapsed exhausted in the midst of an antic dance.

Now I looked more closely and saw that she was not old at all, that in fact she was a maid of no more than seventeen or eighteen.

Why had she been out on such a night? She had no cloak, and wore only a gown of embroidered dark velvet, and felt slippers that would have afforded her scant protection against the cold and the snow. Had she been brought from indoors somewhere nearby and done to death on this spot? She had lain here some long time, for the snow had piled up in a drift against her at one side. It would have covered her all over had not, as I supposed, the warmth of her body, even as it was diminishing, melted the flakes as they drifted down on her. When I touched the stuff of her gown I instantly drew back my fingers, shuddering, for the wetted velvet was brittle and sharp with ice. I was reminded of the frozen pelt of a dead dog I had held in my arms when I was a boy, a house dog that my foster-father, old man Stern, had shut out of doors all night and left to perish in the cold of midwinter.

But this poor young woman now, this slaughtered creature! I could do no more than stand there helplessly and gaze at her in pity and dismay. Her eyes were a little way open, and the pallid light of the stars shone on the orbs themselves, glazing their surfaces and giving them the look of hazed-over mother- of- pearl. They seemed to me, those eyes, deader than all the rest of her.

For long moments I leaned forward with my hands braced on my knees, drunkenly asway and breathing heavily. Now and then I let fall a shivery, rasping sigh. I wondered what strange power the creature possessed, dead as she was. How could she hold me here, even as I was urging myself to flee the spot and fly back to the sanctuary of the Blue Elephant? Maybe something of her spirit lingered within her even yet, a failing light; maybe I, as the only living being round about, was required to stay by her, and be a witness to the final extinguishing of that last flickering flame. The dead, though voiceless, still demand their rights.

Her head was surrounded by a sort of halo, not radiant but, on the contrary, of a deep and polished blackness against the white of the snow. When I first noticed it I couldn’t think what it might be, but now, bending lower, I saw, just above the lace ruff she wore, a deep gash across her throat, like a second, grotesquely gaping, mouth, and understood that her head was resting in a pool of her own life-blood, a black round in which the faint radiance of the heavens faintly glinted.

Yet even then I tarried, in hapless agitation, held there as if my feet were fastened to the ground. I urged myself to turn away, to turn away now, this instant, and be gone. No one had seen me come, and no one would see me go. True, the snow all round was fresh, and my boots would leave their prints in it, but who was to say they were the prints of my boots, and who was there to follow my track?

Still I could not shift myself, could not shake off the impalpable grip of the dead hand that held me there. I thought to cover her face, but I had no cape, or kerchief even, and I was not prepared to relinquish my coat of beaver skin on a night of such killing cold, no matter how strong the natural imperative to shield her, in the shame of such a death, from the world’s blank, unfeeling gaze.

I knelt on one knee and tried to lift her by the shoulders, but rigor mortis and the frost had stiffened her; besides, her gown was stuck fast to the ice on the flagstones and would not be freed. As I was struggling to raise her—to what purpose I would have been hard put to say—I caught a heavy, sweetish fragrance that I thought must be the smell of that dark pool of blood behind her head, although it, too, like the rest of her, was frozen and inert.

When I let go of her and stood back, there came up out of her a drawn-out, rattling sort of sigh. At Würzburg I had studied doctoring for a twelvemonth, and knew that corpses sometimes made such sounds, as their inner organs shifted and settled on the way to dissolution. All the same, every hair on my head stood erect.

I crouched again and examined more closely the wound in her throat. It was not a clean cut, such as a sharp blade would make, but, rather, was ragged and gouged, as if some ravening animal had got hold of her there, sunk its fangs into her tender flesh and ripped it asunder.

I also saw that she was wearing a heavy gold chain, and on the chain was a medallion, gold too. It was circular and large, with flaring edges, a Medusa head, it might have been, or an image of the great disc of the sun itself.

At last I broke free of whatever dead force she had been wielding over me. I turned and stumbled away up the lane, in search of help, although surely the poor creature was far beyond all human succour. Death is death, whatever the priests or the necromancers—if there is a difference between the two—would have us believe, and there’s an end of it, our mortal span done with.

The little houses as I passed them were shuttered and silent, with not a chink of light showing in any of the windows, yet despite the deserted aspect of the place and the lateness of the hour, I had the impression of being spied upon secretly by countless waking, watchful eyes.

My feet were numb from the cold, while my hands, cold too, nevertheless burned under the skin, with a sort of feverish heat. I felt strangely detached, from my surroundings and from myself; it was as though death had touched me, too, had brushed me ever so lightly with an icy fingertip. I thought of the glasses of schnapps—how many?—that I and the old soldier had downed, sitting by the hearth at the Blue Elephant, and I longed now for a mouthful, the merest mouthful, of that fiery liquor, to warm my blood and calm my confused and racing thoughts.

After I had trudged for some way along the base of the castle ramparts, the snow squeaking under my boots and my breath puffing ghostly shapes on the air, I came to a gate with a portcullis. To the right of the gate was a sentry box, inside which a lantern glowed weakly, although in the midst of such darkness it seemed a great light. The sentry was asleep where he stood, leaning heavily on his pike. He was short and fat, with a belly as round and tight as a beer keg. In a brazier beside him there glowed a fire of sea coals, a little of the welcome warmth of which reached to where I stood.

I called out a halloo and stamped my foot hard on the ground, and at last the sentry’s eyelids fluttered open. He goggled at me blankly, still half asleep. Then, coming more or less to his senses, and remembering who and what he was supposed to be, he hauled himself to attention with a grunting effort, his coat of mail jangling. He straightened his helmet and made a great show of levelling his lance and brandishing the blade of it at me menacingly, while demanding in a thick, slurred voice to know who it was that went there and what business I was about.

I gave my name, but had to repeat it, the second time fairly shouting it in the fellow’s face. ‘Stern!’ I bellowed. ‘Christian Stern!’

I should admit that at this time I had a high notion of my own name, for I could already see it embossed on the spines of a row of learned tomes that I had no doubt I should some day write.

The sentry stood gazing up at me, dull-eyed and blinking. I recounted to him how I had chanced upon the young woman, lying on the stones amid the snow under the castle wall, with her throat torn open from the point of one earlobe to the other. Upon hearing my story, the fellow hawked and spat over the half-door a gob that landed with a splat just short of the toe of my right boot. I pictured myself using that toe to deliver the rascal a good hard kick to the soft underpart of his pendulous belly.

‘What’s it to me,’ he said scornfully, ‘if a drab had her windpipe slit?’

‘She was no drab,’ I said, thinking of the velvet gown and the gold medallion on its gold chain. ‘On the contrary, she was a gentlewoman, as I believe.’

‘All the whores in Prague fancy themselves high-born ladies,’ the sentry said with renewed scorn.

My temper in those young days was high and hot, and I considered wresting the lance from the fellow’s grasp and giving him a whack of it upon his helmet to repay him for his insolence. Instead I controlled myself and told him that someone in authority should be notified that a grave felony had been committed.

At this the sentry laughed, and replied that someone in authority had been notified, for hadn’t I just told him, and wasn’t he someone in authority? It was apparent he considered this a rare turn of wit.

I sighed. My feet were almost entirely numb by now, and I could feel hardly anything of them from the ankles down. What, I asked myself, was that young woman to me, and why was I so concerned for her, who after all was no more than a corpse?

Now another guardsman arrived; I heard his boots crunching over the ice before he appeared out of the mist and the snowy darkness, like a warrior’s fresh-made ghost emerging from the smoke of battle. He looked not much of a warrior, though, being thin-limbed, gangly and gaunt. A rusty arquebus was slung over his shoulder. Come to relieve his fat counterpart, he bent on me an eye wholly indifferent as to who I might be and wiped his nose on a knuckle. The two exchanged some words, and the newcomer took up his place in the sentry box, putting down his firearm and offering his scrawny backside gratefully to the brazier and its glowing coals.

Once more I urged the fat sentry to come with me and view the corpse of the young woman and decide what was to be done.

‘Leave her to the night watch,’ he replied. ‘He’ll find her on his rounds.’

If he did not come with me now, I said, I would straightway fetch an officer of the guard and lay a complaint against him. This was mere bluff, of course, but I put so much authority into my tone that the fellow, after another hesitation, shrugged and grunted at me vexedly to lead on.

We made our way back down the lane. The sentry walked with a bow-legged waddle. He was so stunted that the top of his head, as round as a cabbage, hardly came much higher than my elbow.

The young woman’s corpse was as I had left it, and no one had been there in the meantime, for mine were still the only boot-prints visible in the snow.

Beside me, the fat fellow made a harsh noise at the back of his throat and shut one eye and sucked his teeth. He stepped forward and, with a grunt, squatted on his heels. Lifting up the medallion, he held it on his palm and examined it by the faint light of the stars. He gave a low whistle. ‘Real gold, that is,’ he said. ‘Feel the heft of it.’

What is it about gold, I wonder, that all men imagine themselves masters of the assayer’s art? The same is true of precious stones, yet any old chunk of carved glass can be passed off as a gem of rarest quality, as every jeweller, and every cutpurse, will tell you.

Suddenly the fellow let drop the medallion as if it had scorched his palm. He struggled to his feet and stumbled an unsteady step backwards in alarm. ‘I know this one!’ he muttered. ‘It’s Kroll’s daughter, his girl. Christ’s blood!’ He turned to me with a wild look, then peered all about in the darkness, as if he feared a skulk of murderers might be in hiding out there, ready to pounce.

‘Kroll?’ I asked. ‘Who or what is Kroll, pray?’

The sentry gave a desperate sort of laugh. ‘You don’t know Dr Kroll,’ he said, ‘the Emperor’s sawbones and one of his chief wizards?’ He laughed again, grimly. ‘I daresay you soon will, friend.’

And soon, indeed, I would.

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.