Books

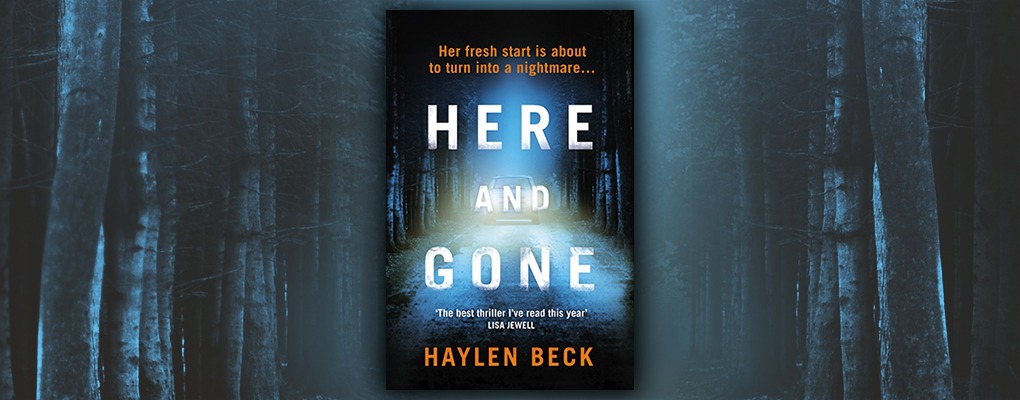

Extract: Here and Gone by Haylen Beck

Here and Gone is the incredible new thriller by Haylen Beck, pen name of prize-winning crime writer Stuart Neville.

Audra has finally left her abusive husband. She’s taken the family car and her young children, Sean and Louise, are buckled up in the back. This is their chance for a fresh start. Audra keeps to the country roads to avoid attention and finds herself on an empty road in Arizona, far from home. She’s looking for a safe place to stay for the night when she spots something in her rear-view mirror. A police car is following her and the lights are flickering. Blue and red.

As Audra pulls over she is intensely aware of how isolated they are. Her perfect escape is about to turn into a nightmare beyond her imagining…

Dark secrets and a heart-pounding race to reveal the truth lie at the heart of this page-turning thriller which we picked as one of the hottest new novels to look out for this year.

Read on for an extract from Here and Gone!

Here and Gone

by

Haylen Beck

5

Audra saw the other cruiser pull away, blurred by her tears. She had watched her children being taken from the station wagon and brought to the deputy’s car, saw Sean’s glances back at her, wept when they disappeared from view. Now Sheriff Whiteside ambled back, his shades on, thumbs hooked into his belt, like there wasn’t a thing wrong with the world. As if her children hadn’t just been driven away by a stranger.

A stranger, maybe, but a policewoman. Whatever trouble Audra might be in, the policewoman would take care of the kids. They would be safe.

‘They’ll be safe,’ Audra said aloud, her voice ringing hollow in the car. She closed her eyes and said it again, like a wish she desperately wanted to come true.

Whiteside opened the driver’s door and lowered himself in, his weight rocking the car. He closed the door, slipped his key into the ignition, and started the engine. The fans whooshed into life, pushing warm air around the interior.

She saw the reflection of his sunglasses in the rearview mirror, and she knew he was watching her, like a bee trapped in a jar. She sniffed hard, swallowed, blinked the tears away.

‘Tow won’t be long,’ he said. ‘Then we’ll be on our way.’

‘That policewoman—’

‘Deputy Collins,’ he said.

‘The deputy, where is she taking my children?’

‘To a safe place.’

Audra leaned forward. ‘Where?’

‘A safe place,’ he said. ‘You got other things to worry about right now.’

She inhaled, exhaled, felt hysteria rise, held it back. ‘I want to know where my children are,’ she said.

Whiteside sat still and silent for a few seconds before he said, ‘Best be quiet now.’

‘Please, just tell—’

He removed his sunglasses, turned in his seat to face her. ‘I said, be quiet.’

Audra knew that look, and it chilled her heart. That melding of hate and anger in his eyes. The same look her father had worn when he’d had a bellyful of liquor and needed to hurt someone, usually her or her little brother.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said in a voice so low it wasn’t even a whisper.

Like a little girl of eight again, hoping ‘sorry’ would keep her father’s belt round his waist, not swinging from his fist. She couldn’t hold his stare, dropped her gaze to her lap.

‘All right, then,’ he said, and he turned back to the desert beyond his windshield.

Quiet now, just the rumble of the idling engine, and Audra was swamped with a feeling of unreality, as if all of this was a fever dream, that she was a witness to someone else’s nightmare.

But really, hadn’t the last eighteen months been like that?

Since she had fled from Patrick, taking Sean and Louise with her, it had been day after week after month of worry. The specter of her husband always looming beyond her vision; the knowledge of him, of what he wanted to take from her, hanging like a constant veil across her mind.

As soon as Patrick knew he had lost her, that she would no longer subject herself to him, he had been circling, seeking the one thing he knew could destroy her. He didn’t love their children, just like he had never loved Audra. They were possessions to him, like a car, or a good watch. A symbol to everyone around him, saying, look at me, I am succeeding, I am living a life like real people do. Audra had realized too late that she and the children were simply pieces of the façade he had built around himself to create the illusion of a decent man.

When she had finally broken free, the embarrassment caused a rage in him that had not faded since. And he had so many dirty strings to pull. The alcohol, the prescription drugs, the cocaine, all of it. Even though he had nurtured those weaknesses in her as ways to keep her tame – an enabler, the counsellor had called him – he now used those as weapons to pry her children away. He had shown the proof to the lawyers, to the judge, and then Children’s Services had come calling, interviewed her in the small Brooklyn apartment she had moved to. Such spiteful, hurtful questions.

The last interview had broken her. The concerned man and woman, their kind voices, asking was it true what they’d been told, and wouldn’t the children be better off with their father, even for a few weeks until she got herself straight?

‘I am straight,’ she had said. ‘I’ve been straight for nearly two years.’

And it was the truth. She wouldn’t have had the strength to leave her husband, taking the children, if she hadn’t got herself clean first. The eighteen months since then had been a struggle, certainly, but she hadn’t once fallen back into the habits that almost killed her. She had made a life for herself and the kids, got a steady waitressing job in a coffee shop. It didn’t pay much, but she had a little money put away that she’d taken from her and Patrick’s joint account before she left. She had even started painting again.

But the concerned man and woman hadn’t seemed to care about any of that. They had looked at each other, pity on their faces, and Audra had asked them to please leave.

And the man and woman had said, ‘We’d rather it didn’t have to go to court. It’s always better to settle things between the parents.’

So Audra had screamed at them to get the hell out of her home and never come back.

She spent the rest of the day in a state of frenzied agitation, shaking, craving something, anything to smooth the edges of her fear. In the end she called her friend Mel, the only friend she’d kept since college, and Mel had said, come out, come to San Diego, just for a few days, we’ve got room.

Audra began packing the moment she hung up the phone. It started as just enough clothes for her and the kids to last the few days, then she wondered about toys, and if they would want their favorite bedding, so the bags became boxes, and she knew she couldn’t fly, it would have to be the aging station wagon she had bought last year, and then it wasn’t going to be a few days, it was going to be forever.

She didn’t stop to think about what she was doing until she was halfway across New Jersey. Four days ago, morning, she had pulled onto the shoulder of the highway, beset by a panic that seemed to explode from somewhere inside her. While Sean asked over and over why she had stopped, Audra sat there, hands on the wheel, chest heaving as she fought for breath.

It was Sean who calmed her down. He undid his seat belt, climbed through into the passenger seat, and held her hand while he talked to her in a warm and smooth voice. Within a few minutes, she had gotten herself under control, and Sean sat with her as they figured out what to do, where they were going, and how they were going to get there.

Smaller roads, she had decided. She didn’t know what would happen when Children’s Services realized she had gone and taken the kids with her, but it was possible they would alert the police and they would be looking for her and the station wagon. So it had been narrow twisting paths to here, countless small towns along the way. And no trouble with the police. Until now.

‘Here we go,’ Whiteside said, pulling Audra from her thoughts.

Up ahead, a tow truck exited the Silver Water Road and steered toward them. It slowed a few yards away, and the driver set about turning it until its bed faced Audra’s car, a warning beep as it reversed. The driver, a scrawny man in stained blue overalls, jumped down from the cab. Whiteside climbed out of the cruiser and met him at the rear of the truck.

Audra watched as the two men spoke, the driver holding out a docket book for Whiteside to sign, before tearing off the top copy and handing it over. Then the driver took a good long look back at her, and she felt like an ape in a zoo exhibit, an irrational anger at his intrusion making her want to spit at him.

As the driver went about his work, attaching a winch line to the front of her car, Whiteside came back to the cruiser. He didn’t speak as he lowered himself inside and put the car in drive. He waved to the tow-truck driver as he passed. The driver took the opportunity to have another look at Audra, and his attention made her turn her face away.

Whiteside took the turn onto the Silver Water exit fast, and Audra had to plant her feet wide apart on the floor to keep from tipping over. The road twisted as it climbed through the hills and soon her thighs ached with the effort of staying upright. The shallow incline seemed to rise for an age, slopes of brown either side spotted by the green of the prickly pears and the coarse bushes.

The sheriff remained silent as he drove, occasionally glancing back at her in the mirror, his eyes hidden by the shades once more. Every time he looked she opened her mouth to speak, to ask again for her children, but each time he looked away before she found her voice.

They’ll be all right, she told herself over and over. The deputy has them. Whatever happens to me, they’ll be fine. This is all a terrible mistake, and once it’s settled, we’ll be on the road again.

Unless, of course, they discovered she had run from Children’s Services. Then surely they would send her and the kids back to New York to face the consequences. If that was the worst of all things, then okay. At least Sean and Louise would be safe until Mel could come get them.

Oh God, Mel. Audra had called her from the road, said they were on their way, and Mel had answered with silence. And Audra knew that the offer to have her as a guest in San Diego had been made in kindness, but without expectation of it being accepted. So be it. If Mel didn’t want them, Audra had enough money left to pay for a week in a cheap hotel. She would figure something out.

One last sweeping bend as the car crested the rise, and a deep basin came into view, a flat bed of land like the bottom of a pan. At its center, a sprawl of buildings. Orange and red scarred the foothills on the far side, unnatural shapes dug out of the landscape below the mountains. Whiteside steered the car down the series of switchbacks, and Audra leaned against the door to keep from being thrown onto her side. Through the window, she saw the first dwellings, prefab shacks and double-wides, among the twisted scrawny trees below. Chain-link fences around the properties. Some had satellite dishes on the roofs. Pickup trucks parked next to a few, others with tires propped against the walls, car parts piled up in the yards.

The sun-bleached asphalt turned to compacted dirt as the road straightened, and the car juddered and rattled. Now they passed the houses Audra had seen from the hillside, and the disrepair became clearer. Some of the owners had done their best to cheer the buildings with bright paint and wind chimes, particularly those with For Sale signs staked in the yards, but she could sense the desperation through the glass.

She knew poor when she saw it because she was only a generation removed herself. Her mother’s parents hadn’t lived in the desert glare, rather the gray skies of rural Pennsylvania, but their dying steel town had the same ragged edges. On the occasions they travelled there from New York, she had played on a rusted swing set in the garden as her mother visited with them, her grandfather years out of work, their last days looming bleak before them.

Audra wondered why this place got the name Silver Water. Must be a river or a lake nearby, she thought. Communities in a desert must have gathered around a source of water. And what kept them here? Who would choose to make their lives in such a hard place where the sun could strip the skin from your back?

The houses on either side of the road grew more concentrated, but still hardly enough to make a street. Among the prefabs, a few more permanent dwellings made of wood, the paint blistering and peeling on the walls. An elderly man in shorts and a vest paused from checking his mailbox to raise a forefinger in greeting to the sheriff. Whiteside returned the gesture, his forefinger lifted for a moment from the steering wheel. The old man eyed Audra as they passed, his eyes narrowing.

An auto repair shop, long since closed down, its signage faded. More houses, aligned along the roadside now, some tidier than others. The road smoothed and widened, and a sidewalk joined its path toward the town. A church, so brilliant white it hurt Audra’s eyes to look at it. She averted her gaze, out through the front windshield, and saw single-and two-story buildings stretch ahead for perhaps half a mile, and she realized the main street lay on the other side of the wooden bridge they approached.

She looked over the railing as they crossed, expecting to see a flowing river. Instead she saw a dry bed, no more than a muddy stream creeping along the middle. The water, silver or not, from which this town had taken its name had withered away to almost nothing. Dying, like the town itself. Through the clamor in her mind, she felt a small sadness for this place and its people.

Dark windows along the main street where stores had once done business. To Let and For Sale signs cracked and faded above many. A general store, a Goodwill place, and a diner were all that still traded. A few side streets crawled away, and from the brief glimpses she caught, they were every bit as desolate. Eventually, at the far end, Whiteside pulled into a lot beside a low cinder block building with the words ELDER COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE in dark letters on a white board. The lot had room for maybe a dozen vehicles, but Whiteside’s was the only one here.

Where was Deputy Collins’ car?

Whiteside shut off the engine, sat still and quiet for a moment, his hands on the wheel. Then he told Audra to wait, and he climbed out. He went to a shallow concrete ramp, enclosed by a railing, that led to a metal door in the side of the building, found a key from the chain on his belt, and opened it, before returning to the car. His fingers gripped Audra’s arm tight as he helped her out and guided her toward the building, a few seconds of blasting heat before the relative cool of the office.

It took a few moments for her eyes to adjust to the dimness in here, the weak fluorescent lights flickering above her head. A small open-plan office, four desks, one with a computer terminal that looked at least a decade old. The other desks appeared to have not been used in years. The desks were separated from the front of the space by a wooden rail with a gate that was bolted shut. A stale smell of disuse hung about the place, a dampness to the air despite the heat outside.

Whiteside kicked a chair out from the desk and backed Audra up to it until she had no choice but to sit down. He took a seat and switched on the computer. It clicked and whirred as it booted up, sounding like an engine that didn’t like cold mornings.

‘Where did the deputy take my children?’ Audra asked.

Whiteside hit a few keys to log on. ‘We’ll discuss that in a while.’

‘Sir, I don’t want to be difficult, I really don’t, but I need to know my children are safe.’

‘Like I said, ma’am, we’ll discuss that in a while. Now let’s get this done. The sooner we get this all straightened out, the sooner I can let you go. Now, full name.’

Audra cooperated through the process of details – her name, date of birth, place of residence – and even when he undid the handcuffs, so he could press her fingertips into an inkpad.

‘We do things old-fashioned around here,’ he said, his tone warming. ‘None of that digital nonsense. We don’t have the funds to upgrade. Used to be I had a half dozen deputies and an under-sheriff to assist with this kind of thing. Them, and a police department, such as it was. Now there’s just me and Collins left to keep this town in order, and Sally Grames, who does admin three mornings a week. Not that we see much trouble. You might be the first person to come through here in a year that wasn’t a drunk and disorderly.’

Whiteside held out a dispenser full of moist wipes, and Audra plucked one from the top, then another, and set about cleaning the black from her fingers.

‘Now, listen,’ he said. ‘This needn’t be a whole big deal. I guess if I don’t put the cuffs back on, you’ll be civil. Am I right?’

Audra nodded.

‘Good. Now, I got some checks to do, make sure there’s no warrants hanging over you, but I doubt there will be. Like I said, the amount of marijuana you had—’

‘It’s not mine,’ Audra said.

‘So you say, but the amount I found in your car might, to some people, seem like more than for personal use. But if you’re civil with me, I guess I can be flexible about that. Maybe call it possession, and forget about intent to supply. So, all things being equal, I expect Judge Miller will give you a small fine and a few stern words. Now, Judge Miller usually holds court on a Wednesday morning over in the town hall, but I’m going to give her a call, see if she’ll come over and hold a special session in the morning for an arraignment. That way, you’ll only have to spend the one night here.’

Audra went to protest, but he held up a hand to silence her.

‘Let me finish, now. I’m going to have to put you in a cell overnight, no matter what. But if you’re cooperative with me, as soon as I got you settled in, I’ll make that call to Judge Miller. But if you’re not, if you give me trouble, I’ll be happy to let you wait a day or two longer. So you think you can be good? Not cause a fuss?’

‘Yes, sir,’ Audra said.

‘All right, then,’ he said, standing. He walked to a door in the rear of the office marked CUSTODY, sorting through the keys on his chain, then stopped and turned. ‘You coming?’

Audra got to her feet and followed him. He unlocked the door, reached inside to switch on another row of fluorescent lights. Holding the door, he stepped aside to let her pass. Inside stood a small desk, its veneer surface chipped and stained, a coffee mug with an assortment of pens on top of it. Beyond, a row of three cells, barred squares with concrete floors, two thin cots in each, and toilets and washbasins screened by low brick walls.

She stopped, the fear that had been bubbling in her beginning to rise up. Her shoulders rose and fell with her quickening breaths, a dizzy wave washing over her.

Whiteside stepped around her, went to the farthest cell to the left, and unlocked the door. Metal‑on‑metal squealed as he slid it across. He turned to look at her, an expression of concern on his jowly face.

‘Honestly,’ he said, ‘it’s not that bad. It’s cool, the bunks aren’t too uncomfortable, you’ll have privacy when you need it. One night, that’s all. I just need you to take off your shoes and your belt, put them on the desk there.’

Audra stared into the empty air inside the cell as tremors worked through her body and limbs, her feet glued to the concrete floor.

He reached a hand out to her. ‘Come on, now, quicker you get in there and get settled, the quicker we can get all this straightened out.’

She unbuckled her belt, slipped it from her jeans, kicked off her sneakers, then placed them all on the desk. Her sock soles whispered on the vinyl tiles as she walked to the cell and through the door. She heard that squeal again, and turned in time to see the door slide closed. Whiteside turned a key in the lock.

Audra approached the bars, put her hands on them. She looked Whiteside in the eye, inches away, on the other side.

‘Please,’ she said, unable to keep the quiver from her voice. ‘I’ve done everything you said. I’ve been cooperative. Please tell me where my children are.’

Whiteside held her gaze.

‘What children?’ he asked.

Intrigued? Find out more about Here and Gone author Haylen Beck in our interview.

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.