Books

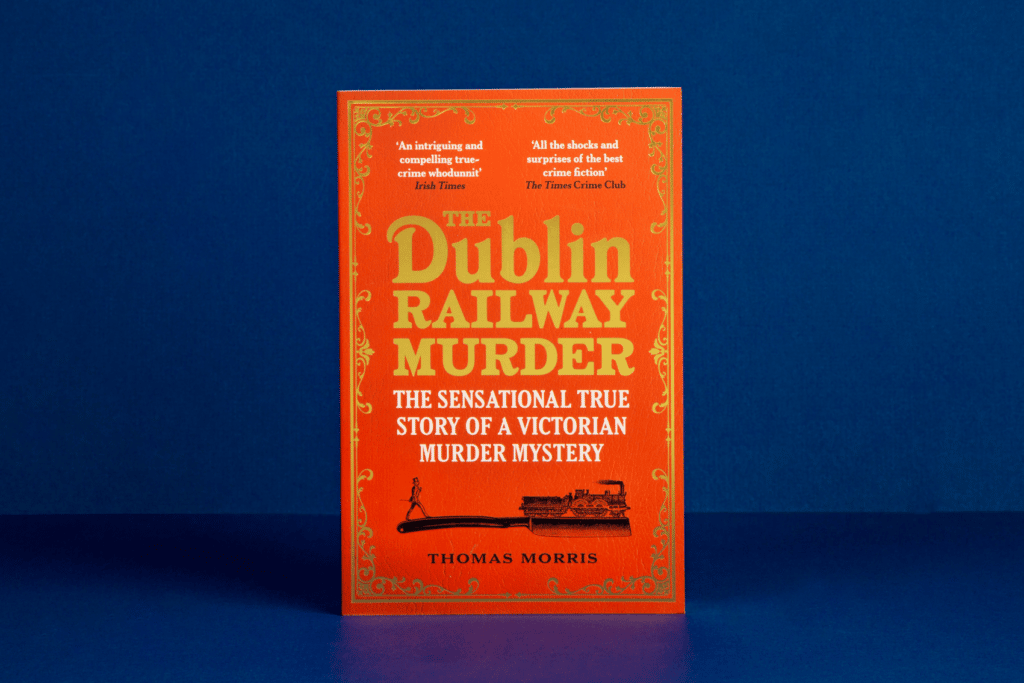

The Dublin Railway Murder: the real life locked-room mystery that scandalised 1850s’ Dublin

When his colleagues broke down the door to his office, they found George Little lying dead in a pool of his own blood. The chief cashier of Dublin’s Broadstone railway terminus had been savagely beaten, his throat cut with a razor. Hundreds of pounds in gold and banknotes lay on his desk, apparently untouched. Who had killed him, and why? And how had they managed to escape the bloody crime scene in one of Ireland’s busiest stations without being noticed?

The murder of George Little in November 1856 scandalised Dublin and led to the most complex investigation ever undertaken by the city’s police force. It was only nine months later, after many false leads, that the detectives finally identified and arrested the prime suspect.

I first learned of this engrossing tale when I stumbled upon a court report of the ensuing murder trial, a sensational event that for a week in August 1857 gripped newspaper readers with its dramatic twists and turns. As I read the transcript I realised that the case contained all the elements of the best detective fiction: an intriguing locked-room mystery, a diverse cast of suspects, the atmospheric setting of a railway station – and even a detective with the striking name of Augustus Guy.

Even better, it was unusually well documented. Murder was such a rare crime in 1850s’ Dublin that the city’s journalists reported every development in the case, however trivial. There were vivid eyewitness accounts of the discovery of the murder weapon, descriptions of the murder scene and intriguing minor biographical details. Even taking into account the likelihood that some of these reports were inaccurate or exaggerated, they provided a clear timeline and crucial incidental colour.

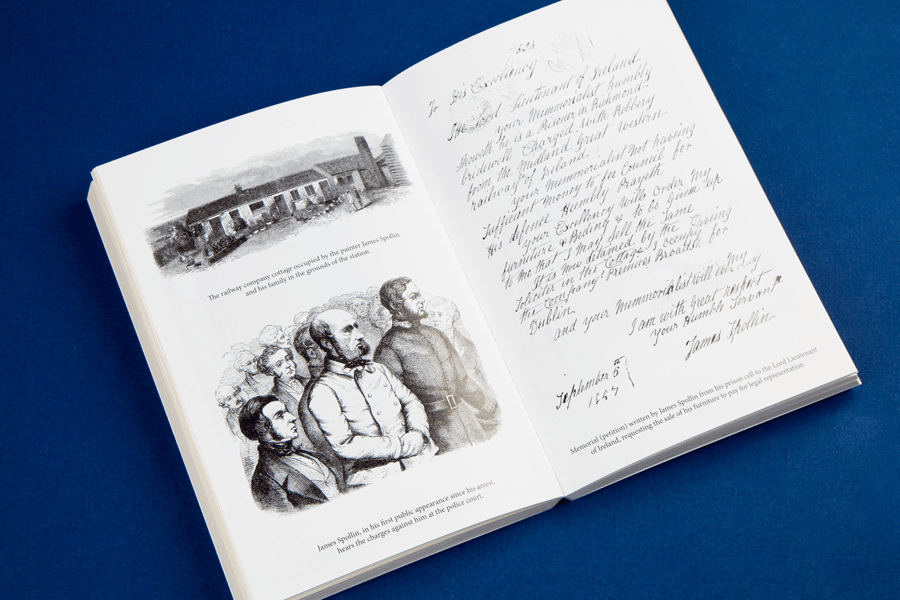

Another rich source was the trial itself. Such was the interest in the case that newspapers published verbatim accounts of the entire proceedings. The transcript was even published commercially, and it was while I was trying to hunt down a copy that I discovered another, far stranger, book about the case. Its author was a Liverpudlian eccentric named Frederick Bridges, a phrenologist – a practitioner of the now-discredited theory that the shape of an individual’s skull gives some indication of their character and intellectual abilities. Bridges was convinced that he could detect a murderer by making a simple examination of their head and attempted to prove it by befriending James Spollin, whom many suspected of being the killer. The pamphlet Bridges wrote about his encounters with Spollin added a bizarre new aspect to the case – and one of my favourite episodes in the entire saga.

These were the main sources with which I set out to write a narrative account of the murder investigation and its aftermath. In October 2019, I visited Dublin to walk among the buildings I was writing about, and to see if there was anything more to learn. I did not hold out much hope that any official documents relating to the Dublin Railway Murder would have survived: most of Ireland’s state archives were destroyed by the fire that ripped through the Public Record Office during the Civil War in 1922.

But I was in luck. In the National Archives of Ireland I uncovered a fat cardboard file packed with contemporary letters and memos, chronicling the entire course of the police investigation and its political aftershocks. It was a goldmine. The documents included transcripts of all the police interviews, allowing me to reconstruct entire conversations between witnesses and detectives. Crucially, the files not only confirmed the main events of the investigation but also revealed what was going on behind closed doors – a parallel tale of police incompetence and government cover-up.

My first impression of the case I narrate in The Dublin Railway Murder was that it was a story worthy of a Golden Age murder mystery. I still think that’s true; but thanks to the miraculous survival of a cache of documents from 1856 I also discovered that the story was far more complex and nuanced – and absorbing – than I could have hoped.

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.