Books

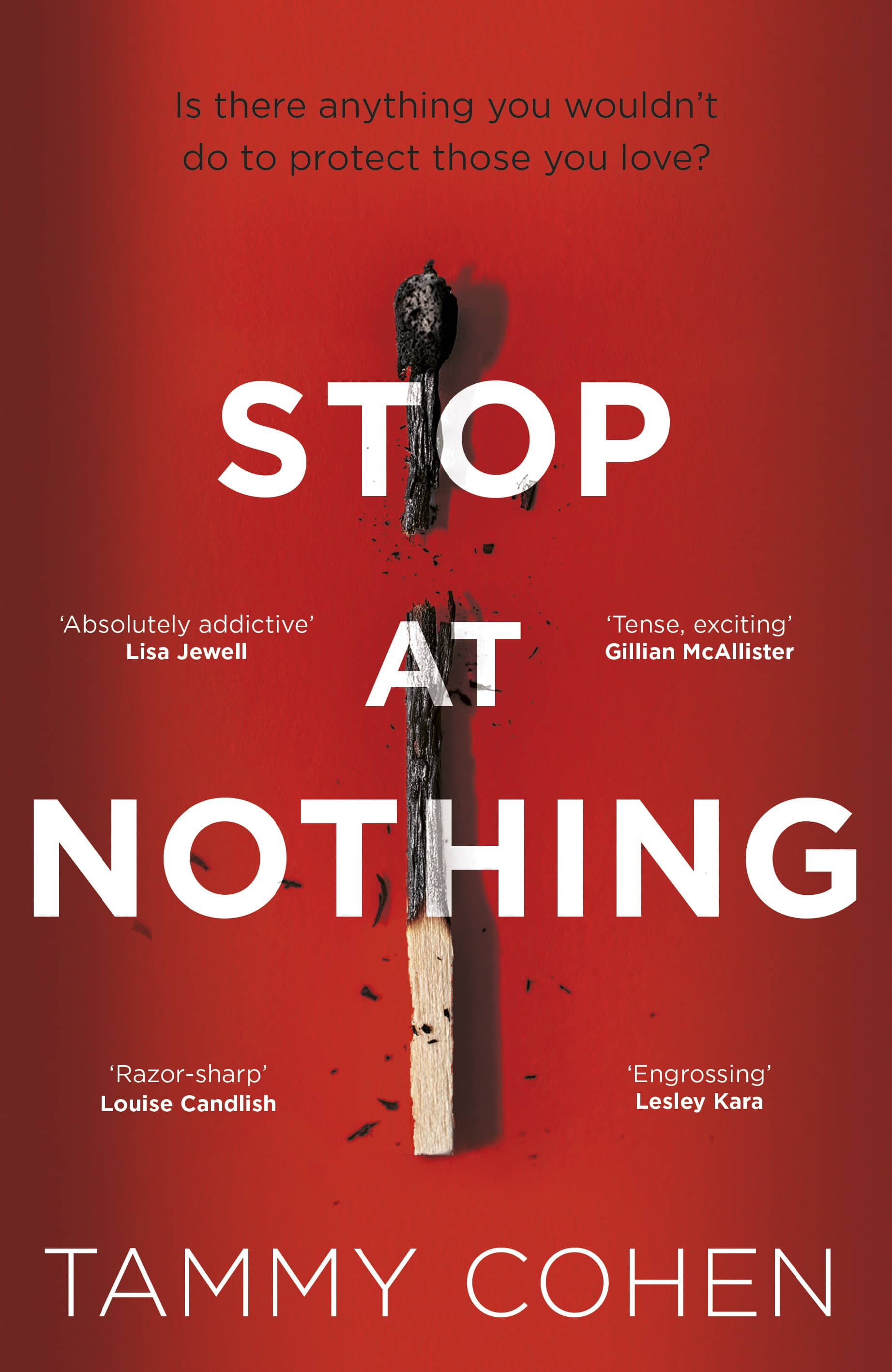

Extract: Stop at Nothing by Tammy Cohen

Stop at Nothing by Tammy Cohen is a gripping, relatable and intriguing thriller perfect for fans of Lisa Jewell, Heidi Perks and C L Taylor.

Tess has always tried to be a good mother. Of course, there are things she wishes she’d done differently, but doesn’t everyone feel that way? Then Emma, her youngest, is attacked on her way home from a party, plunging them into a living nightmare which only gets worse when the man responsible is set free.

When Tess sees the attacker in the street near their home, she is forced to take matters into her own hands. Blinded by her need to protect her daughter at any cost, will she end up putting her family in even greater danger? Because there’s nothing she wouldn’t do to make it right…

Read on for an extract from Stop at Nothing by Tammy Cohen!

Stop at Nothing

by

Tammy Cohen

You know when you have a song stuck in your head that you can’t shake off? Earworm, they call it. Something that wriggles into your brain and gets lodged there. Well, you are my earworm. You have eaten your way along my neural pathways and into my frontal lobe and now my thoughts itch with you.

‘Just say no, you can’t come in,’ Mum says. As if it was a question of looking through the video intercom and deciding not to press the buzzer.

She doesn’t understand that you’re already installed, feet up, kettle on.

I had nits not long ago. When you’re in and out of school every day it’s pretty much inevitable. I can still remember that sensation of my scalp crawling, of something living, uninvited, on my skin.

And now that’s where you live too.

Some days I think I would wash myself in bleach if it would get rid of you.

1

‘You must not speak.’

That was directed at me.

I nodded. I was there only as a silent support.

I was sitting about six feet behind Em, slightly to her right. I could see the rounded slope of her shoulders, the heavy fall of hair over her face, the curve of her right cheek, the hand resting on her jeans, one finger worrying away at the ragged skin around her bitten thumbnail.

There is something about your children’s hands, isn’t there, that goes straight to the most primeval part of you? Some muscle memory ingrained from the very first time their tiny baby fingers gripped on to your own, or when a soft toddler palm reached up for yours in the street – that unquestioned trust that you would be there, waiting to receive it.

As I watched, a small bead of blood blossomed on the side of Em’s thumb, and I had to look away.

The room was windowless. Less a room, really, than a partitioned area off the main floor. Fluorescent strip lights, the same drab dark blue carpet as everywhere else in the building. The air stale and mint-edged from the gum the policewoman chewed so her breath didn’t smell of cigarettes, although her clothes reeked of them.

There was another woman in the room who’d been introduced as the defence solicitor. She had a moon-shaped face and an impassive expression, as if it was all the same to her. My daughter. The ugly thing that happened to her. All the same.

A video camera was bracketed to the wall up near the ceiling, and I deliberately didn’t look at it, though I was conscious of it the whole time.

The policewoman read through the script, explaining what was going to happen. A video would play showing nine different men and Em was to watch the entire thing through twice without commenting, after which she’d be asked if she recognized the man who’d assaulted her.

‘Is that clear?’

Em nodded, but then was asked to say ‘yes’ out loud, for the camera. Then she had to confirm her name. Her voice sounded very small and my stomach felt tight.

The video started. A man with heavy-set features and a pronounced underbite turned slowly to show first his left side then his right and then finally face on.

I sat up straight. Made my expression neutral.

This first man looked nervous. Licked his lips. Concentrated. They weren’t actors. I’d already googled it. They were volunteers who’d agreed to go on a national database in return for a tenner or something. VIPER, they called this identification process. I knew it was an acronym but it also suited the sense of menace I’d felt since this whole nightmare started.

The second man could hardly hide his smirk. I pressed my top teeth down on to the bottom ones so those at the back ground together. Did he think this was funny? My daughter. Only sixteen years old. Was it a joke to him? Neutral face. Silent support.

I was sure I’d have coped with it all better if I’d had more sleep. I’d gone to bed deliberately early the night before, chamomile tea, half an hour’s reading, then lights off. Nothing. Lying in bed, I’d tried being mindful, focusing on the here and the now, the way each part of my body felt in contact with the sheet, relaxing each muscle one by one.

But anxiety whined in my ear like a mosquito.

By the time the alarm went I was a wreck. And now my nerves buzzed like faulty wiring.

Man number three was way too skinny. I could have told them that for nothing. ‘Chunky’ is how Em had described her attacker in her statement to Detective Byrne, the nice policeman, who was currently sitting at a desk in the main area outside. He’d explained why he wasn’t allowed to come in with us. Something about having to be sure the whole process was impartial. He’d worked so hard trying to track down the guy from the CCTV they’d taken from the bus. Perhaps if he was here in the room with us he wouldn’t be able to resist sending some kind of subtle signal when he turned up onscreen. You couldn’t blame him for that.

It was Detective Byrne who came to the house the night it happened. He found Em sitting, crying, on my lap – how long had it been since she’d done that? – the bruising already coming out on her cheek and forehead.

‘Had you been drinking?’ the other policeman had asked her, and I’d been glad she was on my lap because otherwise I might have flown at him, my body charged with shock and worry and all the broken nights.

We were both relieved, when we got to the station a few days later so that Em could give a statement, that it was Detective Byrne who came to buzz us in at the door. Even so, the process had been traumatic.

‘What colour was he?’ he’d asked. And my daughter, taught from birth to be wilfully colour-blind, had been frozen with awkwardness. Even after he’d extracted the description ‘mixed race’ from her, it wasn’t enough.

‘But what complexion exactly? Was he black like me?’ Detective Byrne had skin the colour of the bark chippings outside on the front section of the forecourt.

Em shook her head. In the end he’d used what he called the ‘sliding JLS scale’. He’d called up a photograph of the boy band on his computer screen. ‘Is he more like Aston or Oritsé, would you say?’

Like I said, Detective Byrne was nice.

But Em had definitely used the word ‘chunky’. By the end of her statement I’d built up a pretty good idea of what the bastard looked like. He’d approached her from behind, so she’d only seen a glimpse of him when, before running off, he’d turned to see if anyone was after him. Stocky. Short hair. A pungent aftershave that got up her nostrils.

‘His chin was shaped like a “w”,’ she’d said, and the tissue of my heart had torn softly. She didn’t know the word for ‘cleft’ so she was making up her own description. She wanted so much to be helpful, forcing herself to build pictures of the face she least wanted to visualize.

He’d been wearing a dark padded jacket, she told us. Of course, he would be, I recall thinking, along with ninety-nine per cent of the male population. ‘But it had some kind of logo on the sleeve,’ she remembered suddenly, jubilant at having something to give us. His arm had been around her neck and she’d tried to prise it off with her hands and felt something hard and round on his sleeve. She’d seen it only from the corner of her eye. Some kind of symbol. White, she thought, though she couldn’t be sure.

Now another detail came back to her. When she’d been trying to twist his arm away she’d grabbed his hand and she’d felt a ring. She was sure of it. A metal ring, flat on the top. Chunky, just like the man who wore it.

No, she didn’t know if it was gold or silver. It’d been dark.

Em kept returning to how dark it was, yet in my mind’s eye I saw him crystal clear.

He did not look like man number three.

Man number four had longish dreads. I frowned at the screen over Em’s shoulder. She had described his hair as short. Hadn’t mentioned dreadlocks. Hadn’t they been paying attention? Or was the database really so short on volunteers they had to approximate so wildly?

The fifth man was more like it. Broad, fit, but wary. Barely glancing towards the camera as he turned his head first to one side then the other. As if he had something to hide. I saw a muscle throbbing at his jaw.

I looked at Em, trying to gauge her reaction from the angle of her head. Her right hand was still resting on her leg, though the blood on her thumb was smeared now from being rubbed on the thick denim of her jeans. From the back she could have been twelve years old and I had to fight the urge to reach out and stroke her hair as I used to do when she was little.

Man number six was also promising, though he had the look of someone taking his role too seriously. Frustrated actor, perhaps. People like that must gravitate towards these types of gigs, I guessed. A chance to appear on screen, perhaps for some stranger hundreds of miles away to remark, ‘That one is particularly good.’ He was self-consciously relaxed, if that makes sense. His chin was square, with a hint of a dent. Like I said, promising.

Number seven was a flat-out no. Too dark, too slight. I looked at his delicate mouth. Tried to imagine him hissing, ‘Stop, bitch,’ in my daughter’s ear. Impossible.

Then came eight.

It was like a physical punch in the guts, that first sight of him.

I knew him, you see. I recognized him in some primordial part of me where my daughter and I were still one, where our consciousnesses had not yet divided, where I felt what she felt and knew what she knew.

He was so exactly how Em had described him. Squat, muscular. Skin stretched tight over the bones of his face. He had green eyes. Now that was a surprise. But then it had been dark and she hadn’t seen his face up close. The chin, though. A perfect ‘w’, as if, while he was still being formed, someone had taken a finger and pressed hard. Each corner a mean point of bone. I imagined how it must have felt for Em when he gripped her from behind, those nubs of bone digging into her skull. Of course there was no jacket, and no ring. None of them wore any accessories. No jewellery or distinctive clothing.

But it was him. I knew it instantly.

I glanced at Em. Adrenaline was charging around my body and I wondered if I’d be able to see it in her too. She was sitting up rigid. Where her shoulders had been sloping a moment ago, now they were tensed. I looked at the hand resting on her jeans and saw how the fingers were digging into her thigh, knuckles protruding, anaemic, through the skin. Was I imagining how pale she looked suddenly?

There was a tugging in my rib cage as I watched her concentrating on the screen, just as she’d been told. Not looking away, no matter what it must have cost her to see him again, this man who’d smashed his way into her life, looming up out of the darkness. The bogeyman of her childish nightmares come to life. She knew she had to watch the video twice. She mustn’t give away any reaction. She was doing exactly what was asked of her. But, oh, I wanted to get up then and cross that horrible blue carpet and put my arms around her. My blood felt like it was boiling in my veins. There was no air in that room. Sweat popped on my skin.

This man’s neck was meaty and thick. His arms bulged and strained under his T-shirt. I imagined him hooking one of them around my daughter’s pale, narrow neck from behind. Acid rose up in my throat.

Face on, he looked straight at the camera. Those green eyes shockingly direct. A smile twitched at the corners of his mouth, as if he were saying, Come on, then. What have you got? And I had to dig my nail in my palm because a pulse of hatred shot through me so strong it almost propelled me right out of the chair.

Neutral face. Silent support.

I don’t remember anything about number nine because number eight was still papered all over my eyelids.

After the tape had run, they reminded Em not to speak until she’d seen it a second time. Then they replayed it. This time I didn’t pay any attention to the first seven men. Impatience knitted my muscles together, set my foot tapping against the chair leg.

Even second time around the physical reaction to him was visceral.

I’d reached fifty-two years of age without wishing serious harm on anyone.

I wanted him dead. Wanted to split that cleft chin open, rip tissue from bone.

Afterwards, the policewoman stopped the tape.

‘Did you recognize the man who grabbed you around the neck at 00.15 hours on Friday 12 January on Brownlow Road and repeatedly hit you around the head while trying to pull you away from the main road?’ she asked my daughter. Her voice was flat. Matter of fact. She could have been reading out her shopping list.

Now it was coming. I bit down on my lip, already anticipating the sweet relief of it all being over. Now he would get what was coming to him and we could move on with our lives. For the last four weeks since it happened, we’d felt powerless. Em frightened to come home on her own, even to walk to school. What if he’s still out there? Now the tables had turned.

‘No.’

So certain was I of hearing ‘yes’ that I thought at first I’d misheard, then that Em must have got it wrong. Must have said ‘no’ when she meant the opposite. I sat up straighter, leaned forwards, trying to tap her on the back with my mind, alert her to her mistake. Emma was always inclined to be cautious, particularly where other people were concerned. This isn’t the time for niceness, I wanted to tell her. Number Eight. You saw him.

But instead I remained impassive, my hands on my lap, while the video camera recorded the scene.

Neutral.

Silent.

As we left the video room I saw Detective Byrne sitting at a desk behind a glass partition. He raised his eyebrows in a question then lifted his hand to Em. I remembered how excited he’d sounded when he called to say they’d got an identification on the CCTV taken from the bus that night. Another officer had recognized the man who’d gone through the doors behind Em on the tape. He had spent time inside. Common assault. ABH. There were hints of something more serious, though Byrne wouldn’t be drawn. No sexually motivated convictions. Yet.

‘Isn’t that par for the course?’ I’d asked. ‘Criminals graduating from one crime to another?’ I’d watched enough TV.

Now, I could hardly meet Detective Byrne’s eyes. I felt we’d let him down.

The policewoman showed us out. There were various complicated buzzers that had to be pressed and cards to be swiped.

She told Em not to worry, that she’d done her best. And that if she wasn’t a hundred per cent certain, she’d been right not to guess.

As she held the door open, she stared at me just a moment too long.

‘You look familiar,’ she said.

‘I was here with my daughter a few weeks ago when she made her statement.’

‘Ah, okay. That must be it.’

I turned aside sharpish, but I still felt her eyes on me.

Outside, I threw my arms around Em.

‘You did really well,’ I told her.

There was a knot tying itself inside me, ends pulling tighter.

We started walking, and I couldn’t stop myself.

‘Was there anyone you thought it could be?’

Could she hear it, that knot in my voice?

Afterwards, this moment was something they asked me about again and again. Whether she’d said it unprompted or whether I was the first to mention him.

And even after I told them, they kept coming back to it. How can you be so sure? Wouldn’t it have made sense for you to…? Trying to corral the truth into something different.

But I know what happened. I was there when Em turned to me, hesitant. ‘There was that one guy,’ she began, uncertainty thinning her voice like paint stripper. ‘The one with the eyes. Number…’

‘…Eight,’ I said. ‘I know.’

I grabbed her hand and squeezed.

‘So why didn’t you…?’

‘I just didn’t feel completely sure. They said I had to be certain. But now I feel bad for Detective Byrne, after he went to so much trouble.’

Again that tearing of the soft, worn fabric of my heart.

‘Darling, you did your best, that’s all you could do.’

I kept hold of her hand as we walked on, as if she were once more a child, half surprised that she let me. Her palm was warm in mine, but my mind was elsewhere, focused on a cleft chin, skin stretching like canvas over sharp bones, muscles knotted and obscene under a thin cotton T-shirt.

Where was he now, this man who’d tried to take my daughter from me? Was he going about his life as if nothing had happened? Was he a son, a brother, a husband, an employee, to people who hadn’t the first idea what he was really like? Was he even now hiding in plain sight?

Injustice burned a path across my brain until my head throbbed with it.

2

‘Frances is coming round.’

‘Oh. Right.’

‘Honestly, Mum, could you please try sounding a bit happier about it? She basically saved my life.’

‘Sorry. Obviously, it’s lovely that she’s coming. I’m just surprised, that’s all. I didn’t know you two had been in touch.’

‘She called me just now. She wanted to know how the identity thingy went earlier. You know she did one too. Oh my God, can you stop looking at that thing? Do you know how creepy it is?’

Guiltily, I stopped the Granny-Cam, my parents frozen in place in their living room. Snapping the laptop shut, I glanced over to where Em was standing, feeding bread into the toaster. She was wearing an oversized hoodie printed with the names of everyone in her year that she got after GCSEs last summer and the baggy sweat pants she’d changed into the minute we got home from the police station. Her hair was scraped back into a ponytail and there was a fresh spray of spots on her chin.

She looked heartbreakingly young.

‘You didn’t tell Frances about Number Eight, did you? Because I’m pretty sure it’s illegal for a victim and a witness to swap stories.’

‘God, Mum, I’m not dumb.’

Sometimes, Em sounded so angry with me, not for any particular reason. Just for the fact of me. Perhaps all teenage girls were the same.

The prospect of a visitor forced me to clean the house. The bathroom was disgusting, the grouting on the tiles in the corners stained an orange that no amount of scrubbing could get rid of. I even vacuumed the dog hairs off the sofa with the special attachment I’d never used before. Dotty’s fur was black and white so it showed up on everything.

‘She’s not the queen, you know,’ Em said, watching me from the doorway an hour or so later. ‘Anyway, she’s been here before, remember?’

I hadn’t remembered.

What I mean is, I tried not to remember.

That night. The banging on the door jolting me out of a sleep I had no memory of falling into. Feeling like it was all in my dream. Dotty barking wildly, Em’s face milk-pale, her shoulders shuddering. A young woman I’d never seen before standing on my doorstep with her arm around my daughter.

‘Something’s happened.’ Can there be two more terrifying words for a parent to hear?

‘Do you feel all right about seeing Frances?’ I asked Em now, vacuuming under her legs as she sank down on to the freshly dehaired sofa and picked up the remote. She folded them up underneath her, as she used to do as a child. ‘It’s not going to bring back bad memories, is it?’

Em shrugged. ‘I’m okay.’

‘Because we can put her off, if you’re at all unsure. Tell her it’s not a good time.’

‘Yeah, because that’s nice, isn’t it? Thanks for saving my daughter from being raped and murdered but you can’t come round because it’s not convenient.’

‘That’s not what I—’

The doorbell cut through my justifications.

‘How are you doing… Tessa, isn’t it? Oh my God, I can’t even imagine how hard all this must have been for you.’

I hadn’t properly registered the last time how attractive Frances was, in a wholesome, head-girl kind of way. Thick chocolate-brown hair broken up by tawnier streaks falling to her shoulders. Hazel eyes set well apart in a wide, open face. A small neat nose above a large mouth whose top lip bowed and dipped extravagantly like a mountain range. Strong white teeth, with just the right degree of gap in the front when she smiled, as she was doing now.

‘Oh, I’m fine.’

But then tears were blurring my eyes, and I thought, Really? Is that all it takes? Someone being nice to you?

Of course, it was more than that. Seeing Frances brought it all back. The horror of that night.

I’d been fast asleep. Em said afterwards that they’d banged on the door for ages before I finally woke up, but I’m sure that was an exaggeration. I’d left my phone downstairs. There were seventeen missed calls.

My head still sluggish from sleep, I’d pulled on my dressing gown, but my feet were bare and cold as I padded down the stairs. Dotty was going frantic so I shut her in the living room before opening the front door. ‘Something’s happened,’ said the strange woman who turned out to be Frances. And for a moment I just stood and stared and felt the wind on my bare toes and it all felt wrong and I could not make sense of any of it.

Then instinct took over and I opened my arms, and Em fell into them and buried her veal-white face in my neck. And she was crying. My girl who never cried.

‘Shall we go inside?’ the woman suggested.

We went into the kitchen, me stumbling with my cargo of sixteen-year-old girl. The light seemed blindingly harsh as I sank on to a kitchen chair and pulled Em on to my lap. She buried her head in my neck, her shaking body setting my own blood quivering.

‘Sweetie?’ I asked, moving my head back so that I could see her more clearly. ‘Oh my God!’

A bruise was breaking over her right cheek, livid and purple. White lumps pushed up under the skin of her forehead like knuckles. Her face was stained with mascara tears. My stomach contracted and I felt for a moment that I might be sick.

‘What happened, sweetheart?’

Something’s happened.

The police arrived then. Frances had called them on the way. There were two of them, one black, one white, both wearing big dark jackets and bringing with them a waft of cold from outside. I was conscious suddenly of my dressing gown and bare feet, my legs left unshaven through the winter months.

I felt Em stiffen and take a deep breath. Pressed against me as she was, when she swallowed I felt it as if it were me gulping myself calm.

‘I got on the bus at the top of Muswell Hill Broadway,’ she said in answer to their questions.

‘On your own?’ asked the white policeman, who introduced himself as Detective O’Connell. It felt like a rebuke.

‘We moved recently,’ I said, defensive. ‘Her friends live in Muswell Hill.’

‘And you didn’t feel you should pick her up?’

‘I don’t have a car. I gave her a strict curfew, though. Home by twelve thirty at the latest.’

See how I’m a good parent? See the boundaries I set?

Em explained how, as she’d got on to the bus, she’d been half aware of someone getting on behind her but hadn’t paid it any mind. Her voice was small, but steady. Good girl.

‘You’d been at a party,’ said Detective O’Connell. ‘Had you been drinking?’

I felt myself stiffen, anger rearing up inside, but my thickened thoughts and the solid weight of Em on my lap left me slow to react. Not so Frances, who glared over at the policeman.

‘I really don’t see how it’s relevant whether or not Emma had been drinking.’

I felt myself dissolve with gratitude for this unknown young woman, and she shot me a brief look of support.

‘I’d had a bottle of beer,’ Em said. ‘Maybe two. I wasn’t drunk. I got off at the stop after the Tube.’

Again, she’d been vaguely aware of someone getting off behind her.

‘He’d been sitting at the back, I think. But I hadn’t noticed him.’

Enjoyed this extract from Stop at Nothing by Tammy Cohen? Let us know in the comments below!

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.