Books

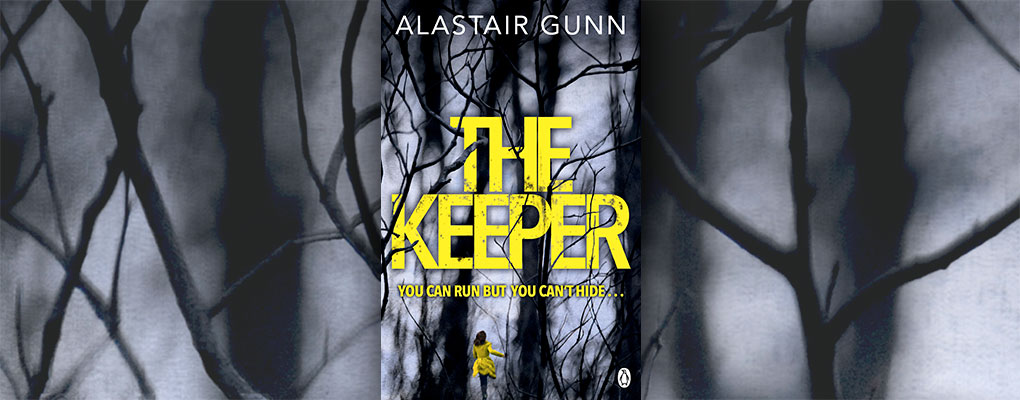

Extract: The Keeper by Alastair Gunn

The Keeper is the brand new novel by Alastair Gunn and the third in the DCI Antonia Hawkins series.

A man is found buried in a secluded wood on the outskirts of London – naked, beaten and bruised. Forensics also show that he hasn’t eaten in the 24 hours before his murder. As more bodies are unearthed in the same state, DCI Antonia Hawkins struggles to find a pattern in the seemingly random killings.

Hawkins is starting to believe that the victims have all been captured, kept and hunted down like animals by a special kind of killer playing a twisted game. And so far, the killer is the one winning.

Read on for an extract from The Keeper!

The Keeper

by

Alastair Gunn

Prologue

He hit the tree hard.

It knocked him off course, scrabbling for grip in the dark as his feet slid on the wet ground. But he stayed up, making it to the next trunk, pulling himself in tight. Fighting for breath; trying not to cough.

The night stretched away in every direction, crooked black shapes bleeding into one another. Shadow on shadow.

He felt sick.

He fought it down. His lungs were burning. He needed time to rest and think. But there was none.

He tried to control his breathing; to calm his banging head. He was shaking. The freezing air tore at his lungs, and he could taste blood on his teeth. His body hurt, the stab of damaged ribs, the arcing wound on his left shoulder leaking sticky wetness down his arm, the screaming pain from his shin. It felt like he’d been running for hours, ducking left and right through dense scrub, wanting to scream for help; knowing it would do more harm than good.

Get a fucking grip.

He wiped his eyes and stared into the gloom, sharp for any movement among the splinters of moonlight filtering down from above. Around him the sinister woods creaked, his attention flicking from one tiny sound to the next; an animal up in the canopy, the slurred rustle of wind in the trees. But still nothing to see except craggy shapes clawing at the night.

How far had he come? It felt like miles, but he might have been going in circles for all he knew.

His head shot round as the cracking noise came from his right; the sound of someone stepping on dry leaves. Someone else moving out there in the darkness.

Not far away.

His breath caught in his throat.

Keep still . . . stay down.

Another crack. Nearer this time.

Panic took over.

Then he was running again, into the blackness.

Where are you going?

He didn’t know.

He pushed harder, skidding across the greasy forest floor, looking for a way out.

And there they were.

Headlights, rounding a bend through the trees ahead, a way off, but worth the risk.

‘Help!’ he shouted. ‘Over here.’

But his voice was weak. The car didn’t stop.

‘Hey!’ Louder. ‘Stop. Please!’

The headlights moved away.

Then he heard someone else running, somewhere behind him in the dark. Another person’s feet pounding the ground in time with his own, someone else’s breath coming in bursts.

Close.

Pete drove himself harder.

Don’t look round; just get to the road.

Then his ankle folded.

He crashed sideways, crying out. There was a white flash, then a ringing sound. He blinked hard. Get up! He tried to right himself, but his muscles had turned to mush, and he slumped back down.

For a second nothing happened as he stared into the darkness, blinking, confused. Had it all been a dream? Was he in bed, sleeping off a night on the sauce?

He tried to twist, felt agony erupt in his shin.

It’s real.

And suddenly there were hands on his throat, strong thumbs clamping his windpipe, choking him.

No!

Pete grabbed the wrists. Clasp and rotate, break the hold. But the grip on his neck tightened, and his vision filled with swirling patterns of red and black.

He forced his eyes open; saw his hands pawing at the arms stretching away. Felt the buzzing panic as his head began to go light.

He was six years old, standing on Brighton Pier, calling for his father to come and put money in one of the rides.

But as the whiteness seeped in, his assailant formed out of the confusion. An alien face, all angles and glassy green eyes. It came closer, its breathing rapid and rough. As if it enjoyed his pain.

What if this is the end?

Then the pain was gone, and the question gently dissolved.

1

There was a painting on the wall of Brian Sturridge’s office, its colours quiet greys and blues, its brass-leaf frame ragged and cracked. It depicted one child teaching another to read from a large, hard-backed tome. It was valueless; the artist unknown.

But, aside from his Mont Blanc fountain pen – a gift from his late father – the picture was the only object that had accompanied Sturridge throughout his thirty-year service, surviving two office relocations and three refurbishments, purely because it epitomised the founding principle of his work: to help or be helped, each party must collude in mutual pursuit of that aim.

And yet, although he would never capitalise on the lucrative potential of his vocation, and move beyond the stuffy confines of counselling within the Metropolitan Police Service, Sturridge found high-ranking officers testing his patience on an increasingly regular basis.

For example, the woman in front of him now.

According to her record, DCI Antonia Hawkins was accomplished, respected, and destined for greater professional heights. She was attractive, with a slim, athletic figure, incredible eyes and dark shoulder-length hair that framed an effortlessly graceful jawline. Attractive enough that, had he not already been down that road and lived to regret it, he might have been tempted. Plus she was young enough – now in her mid-thirties – to change the course of her life if she wished.

So why, when she referred herself for these sessions six months ago, had DCI Hawkins clearly done so with little or no intention of dealing with her considerable and deep-rooted personal issues?

The most likely possibilities were that she agreed to these sessions as a way to avoid something worse, or that she recognised the need for them, without then being able to follow through. Either way, he was growing tired of the lip service she consistently paid his best efforts to help.

Every one of their subsequent weekly meetings had descended into cerebral tennis, with Sturridge attempting to coax her into debate, and Hawkins deftly skirting all the unpalatable subjects they most needed to discuss.

There were two main issues: habitual discomfort with human interaction, and the near-fatal knife attack that had almost killed her ten months ago. Historic difficulties with family and friends, the encompassing need to achieve, volatile personal relationships therefore destined to fail. Sturridge had ascertained all this during their first session. His problem, as often became the case, was getting the client to accept such inconvenient truths.

And the last few moments of silence suggested she wasn’t going to respond to his last question.

He asked it again. ‘How do you feel now . . . about the attack?’

Her gaze lingered on the painting for a second, having followed his there, before she turned slowly back to meet his eye.

Another pause, then, ‘It’s nice. Do you still paint?’

Her usual tactics: pleasantries aired only when the alternative was less comfortable, insight revealed purely to distract.

He sighed. ‘Not since college. It was my final piece.’

‘A pivotal moment?’

Sturridge nodded. ‘Something like that. Did the same thing happen to you?’

‘No.’ Her attention drifted away. ‘It was only ever going to be law enforcement. If I was good at anything else, I’d probably be doing it by now.’

‘Is that why you’re here?’

Her expression gathered. ‘Maybe.’

‘Did the attack change the way you feel about your work?’

Hawkins studied the space between them before replying, her head tilting to the side. ‘I thought about leaving. Briefly, after it happened.’

Progress. ‘Why?’

She thought for a moment. ‘Because it had become personal . . . more than just a job.’

‘So why didn’t you? Leave.’

Hawkins shook her head, as if waking up from a daydream, and whatever spell had inspired her brief mood for revelation was gone.

She shrugged. ‘Never say never.’

2

Hawkins realised she was sucking her teeth as she slowed the car and turned off the main road. She stopped herself, quietly cursing Brian Sturridge and his pious bloody counselling sessions. Surely you were supposed to leave that sort of thing feeling less wound up than when you arrived. So why, after every stupid obligatory visit, did she come away feeling exhausted, as if she’d just been subjected to interrogation?

Probably because it was getting harder each time to skirt the steadily burgeoning elephant.

Eventually she’d have to talk about the attack.

But talking about it wasn’t something she’d been able to do in almost a year since it happened, not with family or friends, not even with Mike, and certainly not with a bored Met counsellor who spent more time thinking about her hemline than her mental health.

Part of her said there was nothing to be gained by baring her soul, anyway, having survived eleven nearfatal knife wounds inflicted by a psychopathic serial killer with a personal grudge. She hadn’t needed time away, once physical barriers had been overcome.

She had simply put her head down and got on with it, returning to lead a major case within weeks; the successful solution of which had earned her permanent

promotion to DCI.

OK, so she had the odd nightmare.

Who didn’t?

Hers might have been recurring, and based on real events, but they had been less frequent recently, and opening up those memories might make things worse instead of better.

What she needed was to forget.

Over the summer, Hawkins had undergone laser surgery to remove the last traces of physical scarring. The treatment had worked so well that even she could no longer tell where the marks had been. But the mental abrasions were taking longer to erase. Her boyfriend Mike had borne the brunt of their effects, but the really rough patches were behind them now, and fortunately he was still around.

DI Mike Maguire, an African American New Yorker, was Hawkins’ closest ally on the force. Over the course of three or four investigations when they’d worked together, a few years ago, intuitive bonds had turned into emotional, then physical ties, before either of them had realised it was happening.

But the news hadn’t gone down well with Hawkins’ then fiancé.

Annoyingly, Mike had done the ‘decent’ thing, taking a secondment in Manchester for six months, giving the couple a chance to sort things out, but Paul hadn’t been able to forgive. He’d moved out a few months later, leaving Hawkins to buy him out of their mutual home; the two-bed semi in Ealing she still occupied.

Mike’s return last winter had led to the relationship being resumed. But she’d been attacked before things had a chance to develop, and one way or another they’d been dealing with the fallout ever since.

For a time afterwards, Hawkins had struggled with intimacy, but Mike’s patience and empathy had allowed trust to be rebuilt, and now their relationship was stable, if as fiery as ever. They’d been living together for almost a year.

Work, however, wanted something more formal.

Mental wellbeing was the Met’s latest byword. The commissioner had signed off a new initiative called Time to Change, a network of services designed to assist officers who experienced traumatic events in the course of duty. For a few months after the attack, Hawkins had been dealing with the upshot from their last major case, and her body healing from the assault. But, as soon as the furore died down, and she was declared physically fit, she’d been summoned by the Mental Health Team for assessment.

Hawkins had ‘not received’ the first letter sent home, and ignored the next, but they were nothing if not determined. An MHT officer had appeared in her office two weeks later to arrange their first meeting.

She had politely informed him that no help was required; everything was fixed. She could cope.

Thanks anyway.

But that had simply pushed them into official channels. DCS Vaughn called her the following day, drawing her attention to the small print in her job description. Basically, she was obliged to attend.

The terms and conditions of her permanent promotion to DCI stated that routine psychological assessments would be conducted biannually, and as required should she be involved in a potentially distressing incident. If she didn’t go, she was in breach of contract, and could be removed from duty henceforth.

She had arrived at the first session defiant, expecting to go through a few motions, tick the relevant boxes; get signed off by appointment number three. Now, six months later, it looked like there was only one way to end her unhappy relationship with the counsellor.

One of these days, she’d have to open up.

Hawkins pushed the thought away as she approached the biggest house on the estate, pausing to let two unfamiliar but expensive-looking Audis pull off the drive. Their presence, along with lingering daylight, emphasised a recent but welcome trend. In the last few weeks, a lighter than usual workload meant that for the first time in years, Hawkins had been able to do shifts vaguely resembling her contracted hours. This, combined with weekly counselling sessions at five in Brent Park, which sat conveniently between work in Hendon and her Ealing home, meant she’d be closing the front door behind her by half six. And for someone who normally rolled in with takeaway food somewhere between eight and ten p.m., that almost qualified as a day off.

Hawkins steered her Alfa Giulietta, a recent purchase inspired by Mike’s love of Italian cars, around the final curve on to her sweeping cul-de-sac. Increasingly she’d been missing the convenience and freedom of having her own transport, but had also wanted something with charisma, so she’d persuaded Maguire to take her around the local forecourts. He’d driven her straight to the Alfa Romeo dealer, and within the hour her search had been over: a top-spec deep blue metallic model with climate control and satnav. She’d written the deposit cheque sitting in the soft leather driver’s seat, silently admitting to herself that, for a Yank, Mike actually had taste. She’d fallen for the looks straight away, and even if the reviews said it was nowhere near the best in its class, compared to the maltreated buckets you normally got from the Met’s selection of pool cars, it was a sodding limousine.

It was a shame that recently she’d been a lot more in tune with the car than with the man who’d advised her to buy it. But tonight was going to be different, if her plan worked.

Hawkins glanced at the passenger footwell, where two bottles of wine were being propped up by the ingredients for an authentic Italian carbonara, and a small but sinful New York cheesecake. Romantic dinner for two, a few glasses of Chablis, and amour might just be on the cards.

Her optimism climbed as the parking area beside the house came into view. Mike’s Range Rover wasn’t there, which meant she could have preparations for the meal well underway by the time he got back from the gym. But the mood stalled when she slowed to turn in, and caught sight of the empty car parked outside on the street.

Siobhan’s tasteless white Nissan Qashqai only ever turned up here for one of two equally sporadic reasons: an obligatory invitation to a family event from their mother, or by complete surprise. Today its appearance was unexpected.

Which meant Siobhan wanted something.

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.