Books

Are some victims less equal than others?

A confession: I’ve killed men, women and children. I’ve abducted, raped, tortured and sent body parts home to relatives, and, hey – the flurry of outraged complaints came only after an aging Border Terrier called Bennie met a sticky end.

Oh, I should explain. These atrocious acts have all played out on the pages of my books. It’s allowed, even encouraged, you see, when you are a writer of crime thrillers. But the seemingly disproportionate response to the dead (fictional) dog got me thinking. Whether in real life, or on the pages of a novel – it seems there’s a pecking order for victims.

Right at the top (although possibly only in Britain) are our furry friends. Next up, cute kids. Some readers won’t touch a book that deals with kids in peril, making it a subject matter many writers prefer to avoid. Riding high at number three are our Goldilocks victims – beautiful young women. The majority of corpses in crime fiction started life as attractive females because they seem to strike the right balance between victims we care for but aren’t too squeamish about seeing hurt.

The list goes on, through nice teenage boys (not hoodlums) young mothers, serving police officers and sweet old ladies, right down to members of the BNP, Tory MPs and convicted pedophiles. We might kid ourselves that justice is blind, but the popular version of it certainly isn’t.

Which rather gets me wondering – does a fictional murder victim have to be nice in order for us to care, to make us want to read on; but not so adorable that we simply can’t bear to?

Decades ago, crime fiction was all about the investigation; the reader pitting his or her wits against the writer, trying to complete the puzzle ahead of time. Back then, the victim was largely irrelevant. These days, though, the crime writer has to engage the reader’s heart as well as his head. She has to make him care about the victim, to identify with him, to get angry and sad on his behalf. It helps a lot if the victim is considered worthy.

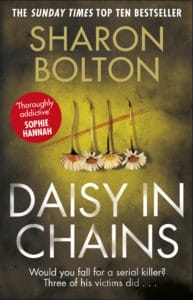

Somewhere on the pecking order of fictional victims, towards the bottom half, I’d suggest, are fat women. I can think of few crime novels in which the victims are fat, largely I suspect, because readers wouldn’t care so much. We might rock along with Meghan Trainor and post supportive comments on the Facebook pages of our larger friends, but the truth is, society simply does not value plus-sized women as highly as it does their slimmer, more attractive sisters and it was exactly this theme I wanted to explore in Daisy In Chains.

Somewhere on the pecking order of fictional victims, towards the bottom half, I’d suggest, are fat women. I can think of few crime novels in which the victims are fat, largely I suspect, because readers wouldn’t care so much. We might rock along with Meghan Trainor and post supportive comments on the Facebook pages of our larger friends, but the truth is, society simply does not value plus-sized women as highly as it does their slimmer, more attractive sisters and it was exactly this theme I wanted to explore in Daisy In Chains.

Hamish Wolfe is my charismatic serial killer serving a whole life tariff in Parkhurst prison for the murder of four obese women. Much of the media and social media speculation at the time of his trial focused on the extent to which the crimes against these women had been allowed to happen by a culture deliberately looking the other way. ‘We’ve become a society in which body size is the last remaining bastion of prejudice,’ writes one fictional blogger in the book. ‘Because fatness has become so despised, we can tolerate the annihilation of it.’

The newspaper articles, news commentary and blogs in Daisy In Chains are all made up, but I came across a plethora of real material online and in print to feed into them.

I found documented cases of larger women being verbally and physically attacked in pubs, on public transport and on the streets. 53 year old businesswoman Marsha Coupe heard the words, ‘you big fat pig’, shortly before she was kicked in the stomach and punched in the face on an early evening train. Large women who are active online talk about a relentless tirade of abuse that even spills over into threats of rape and death. If the blogs are to be believed, fat women get refused entry into nightclubs, they’re abused in doctor’s surgeries and in supermarkets the contents of their trolleys are examined disparagingly.

And all this is being condoned, even led, by those with the powerful, influencing voices. ‘Shouting abuse at fat people is not just fun. It’s socially useful,’ wrote Rod Liddle in The Spectator. He went on to refer to a ‘grotesquely fat woman’ in Sainsbury’s who ‘looked like 26 Ethiopians’ with her ’vile lardy brood’ and joked about setting fire to her. He was being tongue in cheek (at least, I hope he was) but the tone was dangerous, because the more fat people are portrayed in the mainstream media as social pariahs, the more some people will feel justified in attacking them.

One of the darker sides of fat shaming I came across is the assumption that fat women are easy. Because they look the way they do, popular (male) opinion has it that they will sleep with anyone. They aren’t allowed to be particular; they have to take what they can get. Inappropriately touching a fat woman in a bar, grabbing her breasts or her bottom, will be viewed by all around as humorous. Sexual assault? Either she was asking for it in the first place, or she should be grateful anyone wants to touch her at all. Think I’m exaggerating? Google Are Fat Women Easy? and see what comes up.

Our mainstream culture is to be accepting of diversity. We know it’s wrong to be racist, sexist, ageist, homophobic. We don’t make jokes about handicapped people or the mentally ill. Our default setting is to be nice. Except when it comes to fat people. They’re fair game. Why is this?

Partly, I think, because when it comes to the overweight, there are other factors at play. For the most part, people are large because they choose to be so. No one is force-feeding them. Many will argue that they’re setting a bad example to the young, even encouraging the next generation to follow in their footsteps. No one wants to see a playground of chubby children, too exhausted to run around and play; and we all know that obesity has serious implications for our health, at both individual and national level. We feel guilty for our prejudice, condemn the bullying and ill-treatment of people on account of their size; but on the other hand, we wish they’d do something about it. There is a tension between two conflicting societal forces. I don’t pretend to have the answer, but it’s a fascinating sociological dilemma.

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.